|

|

Wisdom in the southeast comes in many forms, even delivered in my native language. As seen parked in front of our vehicle as we left Urfa. “But we have to take your guests there. These are very important saints. You all need a blessing for your trip. It’s the most famous place in Viransehir. Everyone visits; even from other countries. It’s just down this road a little way, not far….” Abit’s cousin Seyhmus implored in his charmingly raspy voice of a much older man, though he’s barely 30. We exchanged glances as he made our decision and turned the car off the main highway that runs along Turkey’s southern border with Syria.

Perhaps he was right. We’d had some unexpected challenges that morning. Back on the road again, we could use some good travel karma. A short detour to see something a local resident thought was so important couldn’t hurt. Some of my best experiences have been spontaneous diversions down an unknown route. Sacred places of all denominations intrigue me; I’ve gone out of my way to light a few candles. Our guests seemed to agree, though maybe they were just being polite and humoring our animated driver, as I translated what he was saying.

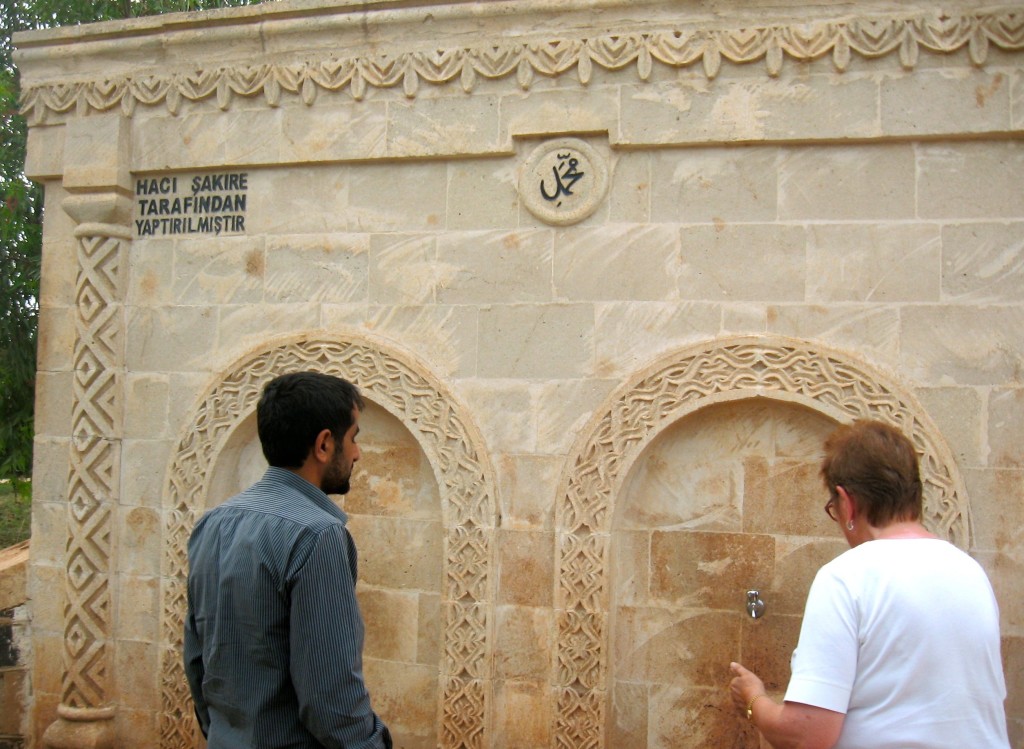

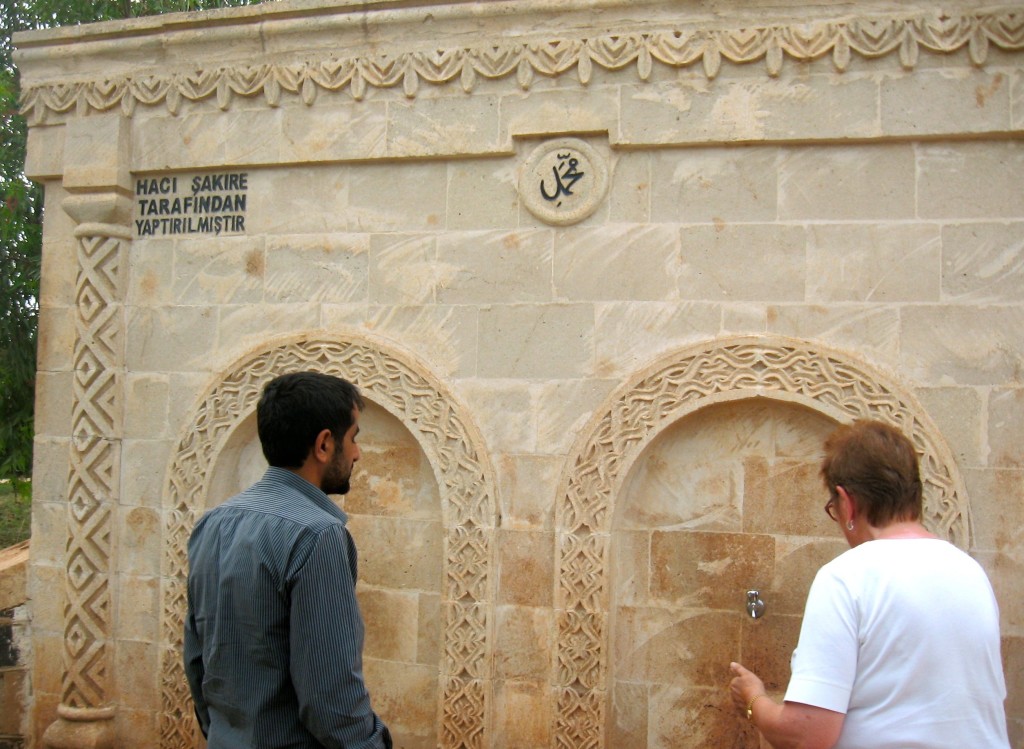

An oasis of ornament in an unexpected place A double triumphal arch marked the road’s entrance. Otherwise, there was not much else around, just occasional road workers raising one lane of the road and repaving it. We were jostling along on the untransformed side, watching the flat waving fields of wheat and lentils spread out around us.

Small talk dwindled as we kept going…10 minutes, 15. Murmured asides about being kidnapped in eastern Turkey, as we saw only a few other vehicles on the road, and no obvious landmarks appeared before us. 20 minutes turned to 30, or so I conjectured in my head. I’d stopped wearing a watch years ago. With an attachment to my laptop and the call to prayer 5 times a day, I didn’t need one. I could see how that made some visitors think I’ve fallen victim to Turkish time.

Patience in the back seat wearing thinner, we passed a large school building, like a child’s drawing of brightly colored paint. A small military police station was opposite, with two soldiers visible, guarding the empty terrain. A few kids playing nearby, but otherwise no evidence of any villages around to supply such a school with enough pupils. Beyond, more open fields, mostly green still this early June, but starting to tinge with gold along the side of the road to match the hills on the horizon.

Another 10 minutes, or maybe time just seemed to lengthen in the heat and dust, conversation stalled and a Kurdish folk singer lamenting his losses on the radio. A flash of black and white as our car’s wheels crunched gravel, scaring a bird out of its nest, its whirring wings like a dervish of light and dark against the stalks of gold wheat.

Finally we turn slightly to the left, as a large grove of old olive trees came into view, along with Eyyüp Nebi, a small village of simple concrete homes. “Okay, we’re here!” Seyhmus said, jerking the car into park.

We filed out, happy to stretch our limbs. A short stroll away down a dusty dirt square – more of a crossroads really, with smaller lanes leading out into the village – we follow Seyhmus into a small paved courtyard covered in trees, a mix of olive, mulberry and hibiscus. I asked Abit, “So, you’ve been here before right?” He just smiled. “You’ll like it. It’s old, they are saints.”

The first tomb was under renovation, workers placing blocks of carved tulips into a low wall, scaffolding still covering part of the small domed structure of cream limestone. A few pilgrims, a family of several generations, the women wearing somber headscarves and bundled twill trench coats, were removing shoes before entering the tomb. It seemed too crowded to try to enter, and the men sitting inside looked none too welcoming, even if we foreign women knew which entrance to use. I felt intrusive, not even taking a photo.

So we wandered around the back to admire the green trees and large garden that spread out well beyond. Seyhmus and Abit beckoned for us to return to the tomb, but we could see inside through the arched windows, to the draped coffin with a green and gold embroidered cloth.

What could be so important about this broken old boulder? Beyond was another small structure of horizontal black basalt and cream limestone, this one half perforated by black ironwork. Inside an oval patch of mossy red earth held a large cracked boulder. Zen garden, Mesopotamian style?

By then, a group of curious local girls had come down from a shady hillside nearby to giggle and ask questions in basic English. Sisters, gold hair and green eyes, with their younger cousins, black eyed and olive skinned, were delighted two of us foreigners could speak Turkish. The oldest girl was practiced, telling us this saint had lost everything, had he lived through his ordeal – pointing at the sign – right here, on this boulder, for years, abandoned by his family. My Catholic upbringing was stirring up memories of Old Testament stories. I knew that Islam shared the same saints and prophets. Who was this saint again?

Ordeal. The word of the day Sabır. I’d learned the word meant patience. A crucial word to know early on living in this culture, where very little was in my control; sometimes going along for the ride was often the best way to be. I’d been told too many times sabır ol – be patient. Calm down, let things happen.

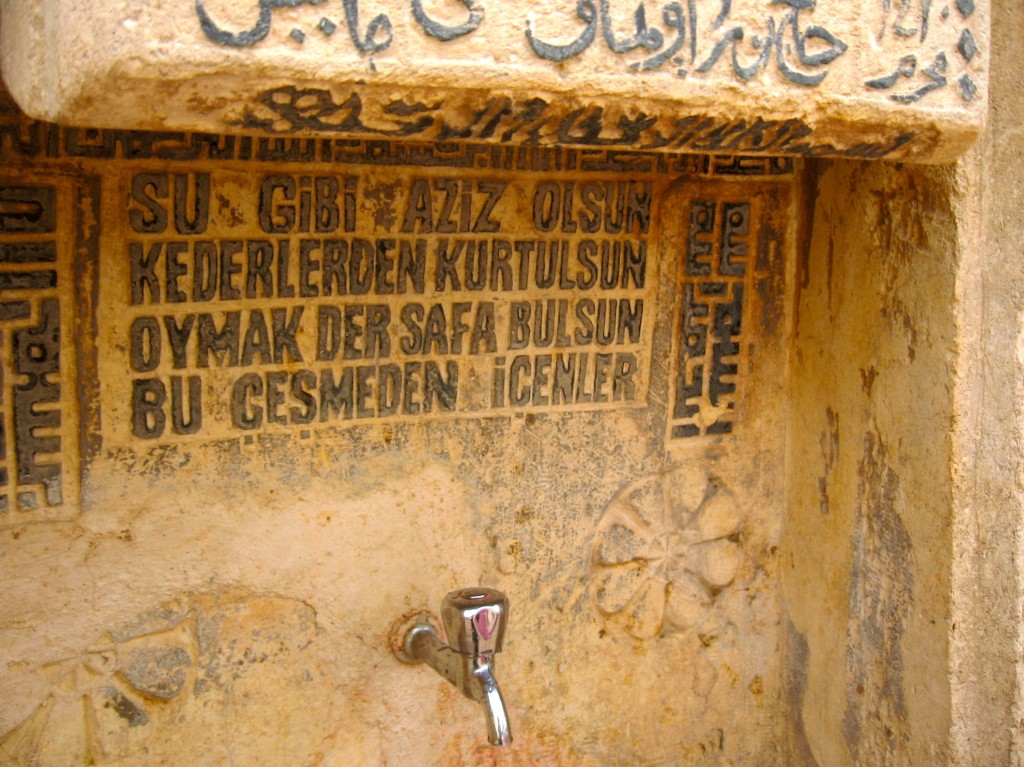

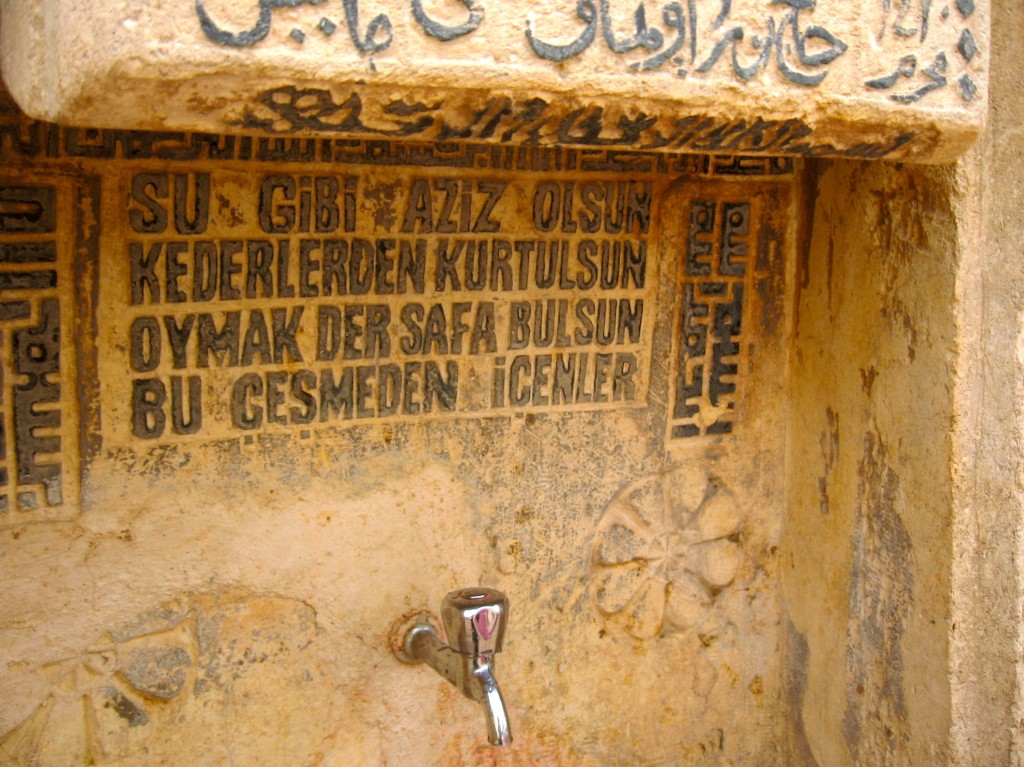

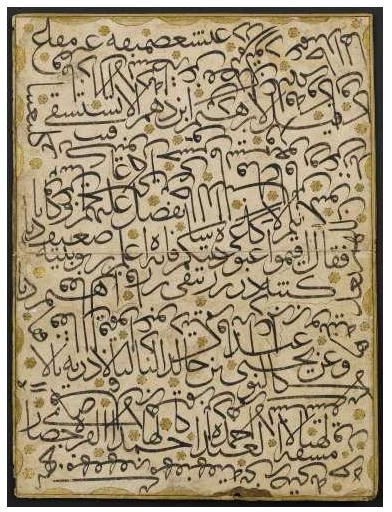

“Healing water” A final monument, this time enclosing a small fountain of “healing water” according to the sign. Though it all looked ancient, the top was only placed in 1999, the year I moved to Turkey. Below there was a verse in modern Turkish I could partly decipher, among the Ottoman, Arabic and Kufic scripts:

Su gibi aziz olsun kederlerden kurtulsun oymak der safa bulsun bu ceşmeden içenler

May the saints save drinkers from this fountain from grief …and something else about “carving that tells of the purity found”.*

A mangled translation, but sometimes it’s enough just to understand the essence, not every literal word. Turkish and English are too different, so opposite in their structure and expression. “Patience is the key to paradise” in this country full of sayings, set phrases and proverbs.

* A far more accurate translation, from a woman brave and talented enough to translate Turkish literature into English:

Good wishes for water,

Oymak bids that all who drink here

Be freed from worries

And find pleasure

To be “protected from grief” was not quite a good enough reason to drink the water… We went through the motions of washing our hands and faces, though only Abit and Seyhmus were brave enough to drink the water.

Follow the signposts, or leave them? Slowly strolling back to the car, still hot and mystified by the visit, one of our group noticed a sign with the saints’ names, overlooked in our haste to get out of the car.

“OH. Eyyup. That’s Job!!!”

Suddenly the meaning of the fountain and the boulder became clear. Patience to come through an ordeal. Now I understood Sehymus’ desire for our visit, his bafflement why we had not immediately agree after our delayed morning. We were all “people of the Book”; this was our story too, something we had in common. Laughing as we piled back into the car, I hoped to keep the lesson of this day with me the rest of the trip.

We continue our Turkish Tulip Trip…to Gobekli Tepe, Harran and Urfa.

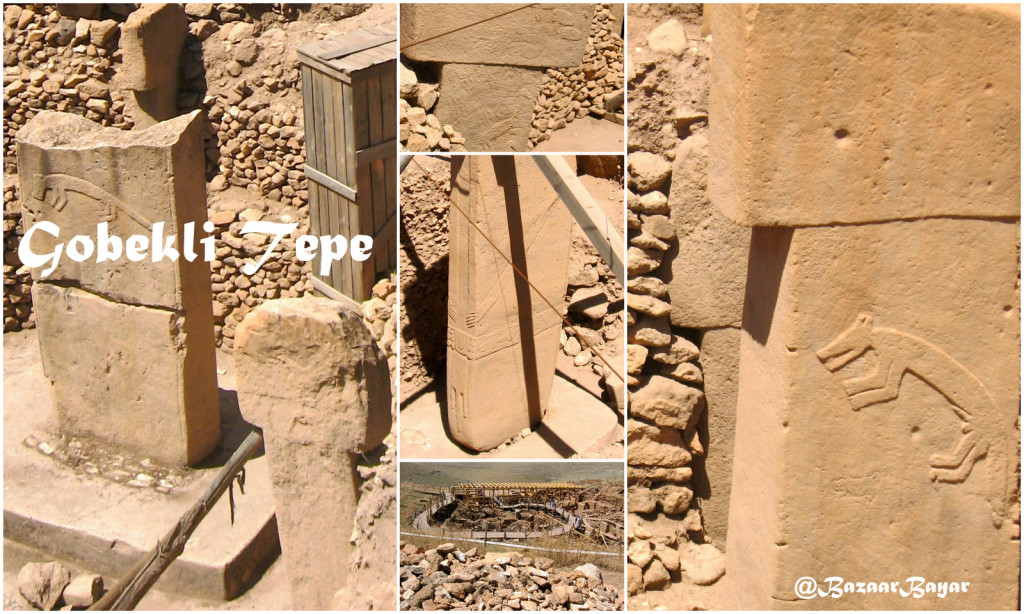

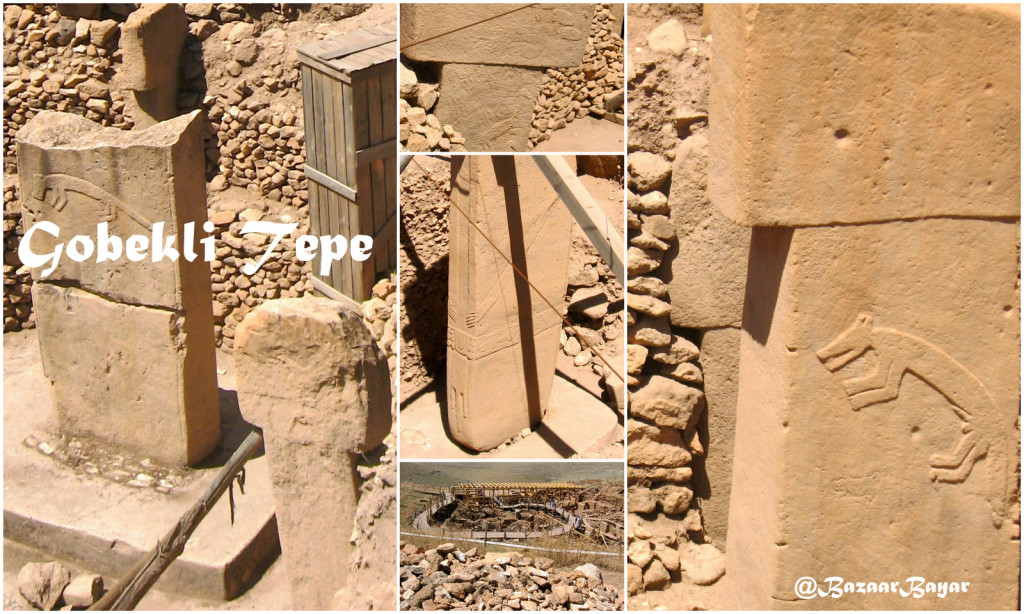

Gobekli Site The depth of history in the Turkish Southeast is truly mind-boggling. Nowhere is that more clear than at Gobekli Tepe, believed to be the world’s oldest temple, at an estimated 11,600 years of age. That’s 7,000 years older than Stonehenge. According to National Geographic, Gobekli Tepe may well be where “the urge to worship sparked civilization”.

The site is quite isolated, only about a tenth of it excavated so far. Three Stonehenge-like rounds of 6 meter/18 foot high pillars are arranged in a circle around two more substantial pillars protecting portals in the floor, possibly gateways to the afterlife. Work began on the highest hillside, with another hill nearby which looks like a natural amphitheater. Basic diagrams explain in Turkish, English and Arabic that there are believed to be another 23 or so such rounds waiting to be unearthed. Evidence of those are scattered around the hilltop, shallow pockmarks about 8″/20cm in diameter, seemingly ‘drilled’ into the stone by an unseen giant hand.

Gobekli Tepe Carved Animals Asymmetrically placed carved animals grace the sides of several pillars. A flock of ducks, a fox, a lizard-like creature, plus at least two human male forms, perhaps depicting dancing priests with belted loincloths and long arms wrapping around the pillars, are clearly visible. Our visit was at midday, making good photography difficult. The much publicized pics from National Geographic were far more theatrical, with dramatic lighting and skewed points of view, which I think will have some visitors walking away disappointed.

The circular wooden ramps constructed for visitors make it impossible to get too close, but it’s an interesting perspective to be looking down on such massive structures. No tour buses there during our visit, just small vans bringing Turkish academics from Ankara, plus a few curious Europeans. Gobekli Tepe, which means ‘potbelly hill’ in Turkish, is for now a site for diehard archaeology and mystery lovers, and will be fascinating to revisit as more is learned.

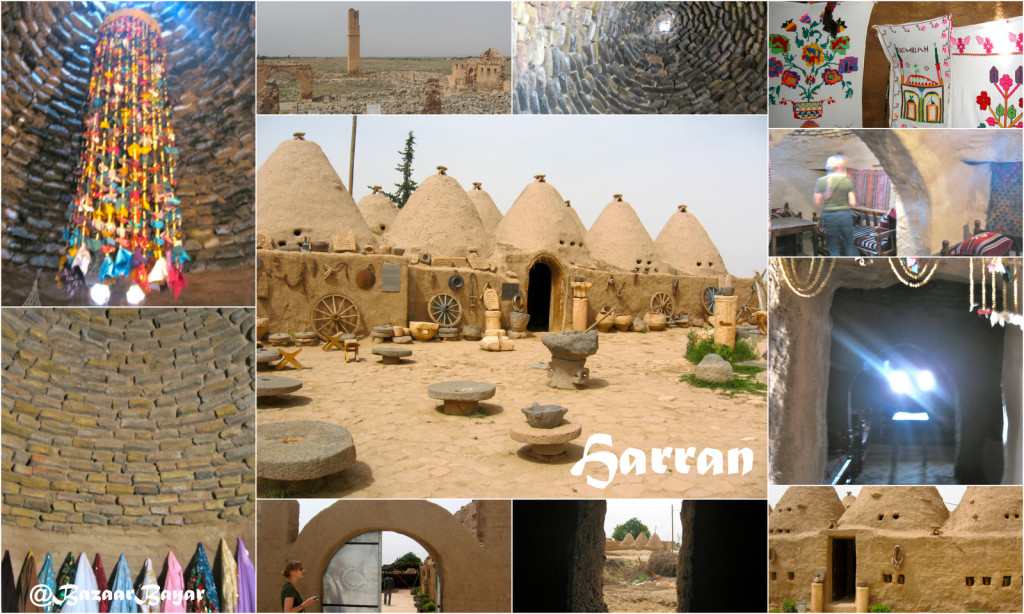

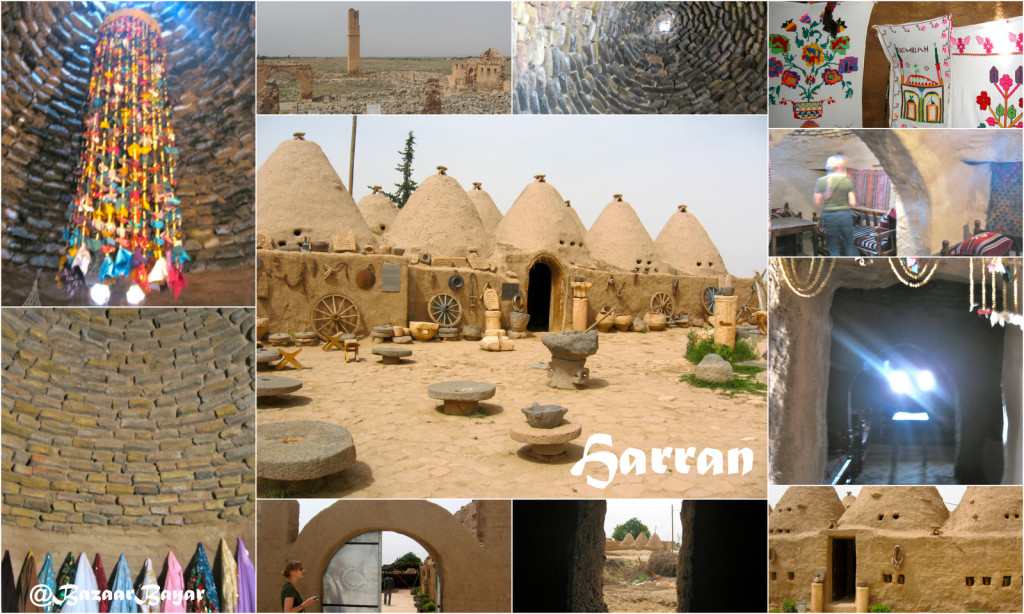

Moving forward on humanity’s timeline, we visited another site of major importance in Al-Jazira, this region of upper Mesopotamia. Harran, a merchant outpost begun in the Early Bronze Age, was crisscrossed by so many ancient cultures I won’t even try to make sense of them here. From the early worship of the Mesopotamian moon god Sin, to being the seat of an Islamic caliphate that ruled from Spain to Central Asia, to hosting the world’s first university, where scholars preserved and translated the scientific and philosophical works of the Classical Greek world into Syriac and Arabic, Harran today is dusty, forlorn place.

This ancient city is best known for its ‘modern’ era beehive houses made of unreinforced adobe, only a few remaining for show in this 3,000 year old architectural style. In the blazing sun of early June, they were cool inside, and surprisingly spacious and well lit by natural light coming in from an aperture on top and rows of small square windows. Adobe bricks formed circular domes over our heads, supported by square rooms open to each other by wide arches. I would have lingered longer here, since many of the walls were draped in hand stitched embroideries and weavings, but we were given the hardsell by a family of mostly women and children, who when we refused to buy souvenirs, insisted we eat a suspect lunch of watery stew outside under sparse shade in the heat.

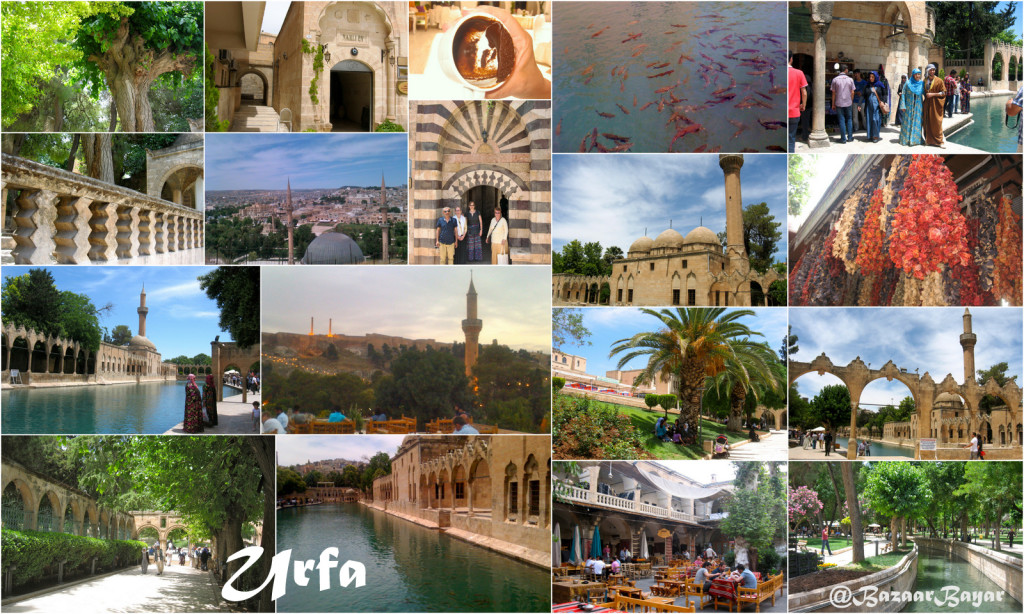

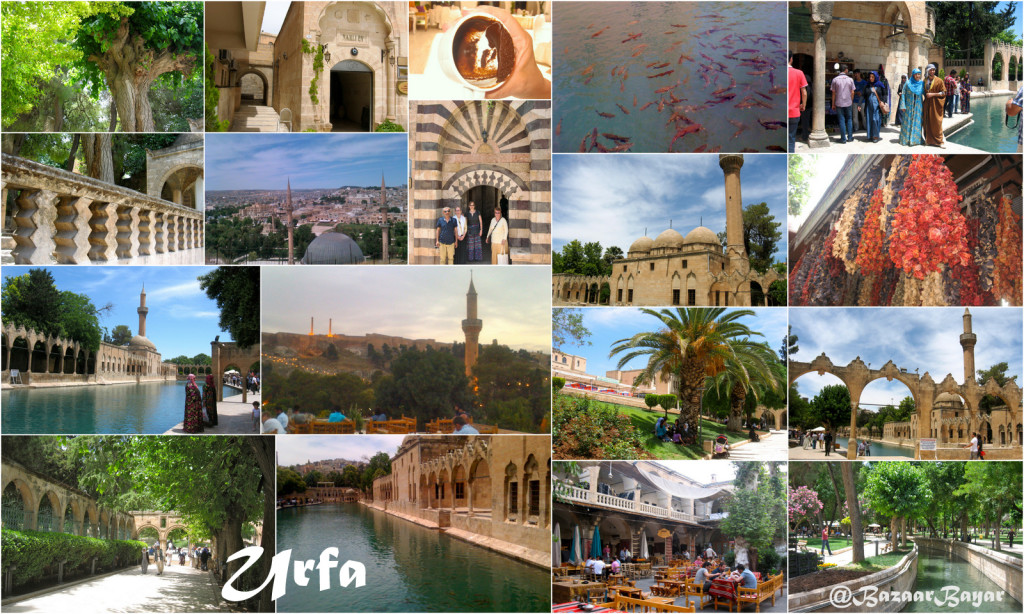

Urfa We spent the night in Şanlıurfa, ancient capital of many names including Byzantine era Edessa, populated today by citizens of Kurdish, Arabic and Turkish origins. By now on our trip, that word ‘ancient’ was meaningless, better used for describing my weary body. Thankfully, the center of the city was surprisingly cool because of greenery and water, the pool of sacred fish. King Nimrod – not to be confused with Mount Nemrut – but the great-grandson of Biblical Noah and possibly the builder of the Tower of Babel, is the villain in this legend. A ruler jealous of Abraham’s increasing influence – THAT Abraham, father of the three faiths, believed to have been born nearby where the large domed mosque now stands – Nimrod had Abraham burned on a pyre. But God turned fire into water and coals into fish. We bought small dishes of pellets to feed those descendants. Years earlier when we had visited, a restaurant had served grilled fish in the garden here, but it has been replaced by a teahouse.

We were charmed by crowds of strolling families wearing Biblically traditional, sparkling bright clothing, until we realized the outfits were mostly costumes rented at a waterside kiosk by tourists from Turkey, Saudi and Northern Iraq. Urfa is a city with huge covered bazaar and coffee houses far more numerous than in Western Turkish cities. We recovered our strength buying spicy Urfa peppers, then drinking the regional wild pistachio coffee, “Menengiç kahvesi”. We read our futures in the grounds, while an ancient faced kid sang melancholy songs for money. Abit bought his first set of double-breasted Kurdish vest and Şalwar, the baggy wool traditional trousers, and we retired to a stone mansion turned chic modern hotel for the night.

Our first journey in the Southeast, after flying from Istanbul to Urfa and spending a quiet village evening. The Turkish Tulip Trip travels to Mount Nemrut.

We set out early morning by van to traverse the Euphrates, taking a small ferry a short distance across the longest river in Western Asia, one of the two major rivers of Mesopotamia. The river’s name is a mixture of Greek borrowing from the old Persian, like many places and cultures in this region of historic hybrids.

Fording the legendary Euphrates River Our excursion continued in search of remnants of past cultures, found where we cooled our feet under a massive 1,800-year-old Roman Cendere Bridge, constructed for Emperor Septimius Severus according to the Latin inscriptions. The winding road beyond climbed in altitude, circling north of an enormous dam, Turkey’s largest. The Southeastern Anatolia Project (Güneydoğu Anadolu Projesi, known by its acronym GAP) began in the 1970s. Dam projects in this region continue to dot the mountainous landscape, flooding villages and diverting water from anyone living south for more populous places in the west.

Crossing Roman bridges: 2nd Century Cendere Bridge built for Septimius Severus, plus the nearby Karakus Tumulus and Arsameia Stele. Revealed next were odd appetizers of even more ancient history from the kingdom of Commagene, a cultural combination of Greek, Persian and Hittite elements founded north of Syria and the Euphrates after Alexander the Great’s empire crumbled. First, a stroll around the Karakuş Tumulus, a hilltop burial site for the royal women of the kingdom.

We then descended into a steep narrow ravine and climbed a short way by foot up a rainy trail to the Arsameia Stele. 1st Century BCE Arsameia had been the capital of the kingdom. Beyond a hillside cistern, Greek inscription and a memorial stele or slab depicting King Mithridates I in royal costume shaking hands with a naked Hercules, nothing remained of the royal city.

Winding along steep roads toward Nemrut Dağı The long day’s journey continued, landscapes changing from rolling green meadows to sharp mountain peaks. The only reason the Commagene are known to more than historians today finally loomed on the horizon: Nemrut Mountain, our final destination. Though one side of the mountain had a brick paved road suitable for the small tourist vehicles that bring hearty trekkers between May and October when the mountain is not covered in snow, we approached from the back side up an increasingly steep and winding road covered in gravel left from the winter.

At the end of the road, we prepared for a fairly strenuous climb, donning jackets and scarves against a strong breeze and cool temperatures at high altitude. Workers were slowly laying travertine pavers on the trail that led to the top, while other parts of the path remained well packed earth bordered by wildflowers and loose stone. Meanwhile, belligerent and probably tired donkeys lumbered by, carrying those not wanting to make the 45-minute effort up under their own steam. Slowly, pausing to take in the vertigo-inducing views, we arrived at the Eastern Terrace.

Eastern Terrace From the notes for the documentary Throne of the Gods: “At 7,700 feet above sea level and containing a 150-foot high tumulus flanked by colossal statues, the Mount Nemrud sanctuary has become synonymous with absolute grandeur.”

The heads of Greek, Persian, Armenian and Hittite gods, along with the likeness of the ambitious Antiochus I (69–34 B.C.) himself, were carved from solid blocks of rock, some as heavy as 9 tons and reputedly brought up the mountain from a distant quarry, were lined up below the altar of bodies from which they’d tumbled. More orderly now than in our previous visits, when the statues could be climbed upon, we heard plans that they’ll be taken to a museum being built below, and replicas erected in their place. After surviving more than 2000 years on the isolated mountaintop, perhaps tourism is doing more damage in a shorter time.

Nevertheless, the interest of foreign visitors was the reason this huge Hellenistic era construction was unearthed, and daily visitors now are a recent phenomenon. In fact, our first visit in 1999 had us stopping to ask several times along the way, since no one knew what we meant when we asked about seeing the giant stone heads. Without the curiosity of German explorers a century ago, or even more, the courageous efforts of a woman from Brooklyn in the late 1940’s, Theresa Goell, who insisted on solving the mystery of the mountain, the monumental mausoleum of Commagene kings may well have remained elusive beyond 2 millennia, silent and windswept.

Western Terrace The Western Terrace revealed more gods – Apollo, Zeus, and Fortuna among them – scattered and illuminated by the setting sun. Most remarkable was what lies between the two Terraces: a 1500 foot high pile of small stones creating an artificial mountaintop, presumably covering the vault where the remains of Antiochus I and perhaps other royalty were laid to rest. Though the entrance has been discovered, the small stones cannot be disturbed without causing a precarious landslide. An ingenious way to make sure a tomb’s riches are never removed and tantalizing to consider what may be inside.

View from the top Like the pyramids in Egypt or the Great Wall of China, built at the obvious expense of thousands of laborers’ lives to command respect and show power, Nemrut is well worth a visit. Not just to see evidence of massive human endeavor but to experience the hubris required, stone by stone, for such attempts at self-deification. Few will remember anything about the particular men who built these monuments, but rather marvel at the effort of the common people who made them.

Bosphorus view from the Sakıp Sabancı Müzesi Terrace, Emirgan A series about our spring Turkish Tulip Craft + Culture Trip: Istanbul along the Bosphorus

Beyond the protected Old City (at least in Sultanahmet, since other parts of the Fatih penisula are currently being ‘rearranged’) is the rest of European Istanbul, to the north of the Golden Horn. On our Tulip Trip, we traveled north up the coastal strip. A place to see and be seen, with upscale crowds understandably wanting to enjoy this lovely environment of parks, palaces and rare green space, though marred by honking cars and polluting buses.

Why aren’t there more small water transports here I wonder, each time I’m caught in traffic. I suppose crossing the Bosphorus by gondola would be suicidal: no Russian tankers or Ukrainian cargo vessels in the Grand Lagoon. And perhaps a fleet of water taxis along the shore would be too unruly, given how drivers behave on land.

Embroidered pomegranate abundance, 18th C Ottoman These expensive Bosphorus neighborhoods are home to strait side mansions converted to museums, two of which we visited. The first took some time to reach, up that busy stretch of scenic coastline all the way to Sariyer: the museum in honor of Sadberk Koç, born into a prominent Ankara family a century ago. She married a cousin who became a major force in the newly forged Republic of Turkey’s educational and cultural institutions, among several others. Sadberk Hanim, a passionate handcraft collector, reflected the image of a tradition bound lady from the Turkey’s first wealthy industrial class of the 20th century.

The long tradition of Turkish handcraft as part of everyday life, 18thC tea towel Our second stop was the Sakıp Sabancı Müzesi, founded by the family of an early 20thC wealthy trader with cotton picker humble origins from the central Anatolian town of Kayseri. The Sabancıs purchased an historic building, former home of Egyptian governors and Montenegrin ambassadors, to house an expanding and influential collection of fine art.

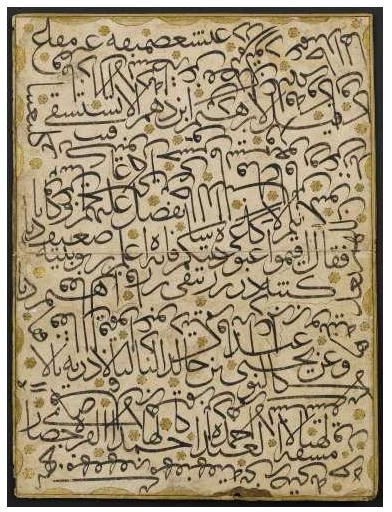

Calligraphy exercise @Sabanci Muzesi The Istanbul Dream: Provincials in a budding democracy prospering through hard work, ending up a generation later in these yalı, the wooden mansions of the long Ottoman reign. That 600 year empire was reduced in relevance as modern Turkey emerged. 90 years on, these mansions take on renewed vitality as the age of the Sultans is no longer ignored.

In this stunning ancient city, the past decade’s economic boom has rapidly changed the landscape beyond this rarified waterside region. A newer wave of arrivals combine Islam with capitalism, as the Anatolian Tigers, prospering cities in the Turkish heartland, send their residents to this eternal melting pot.

Handloomed patterned silk velvets from Uzbekistan, Grand Bazaar A city that has exploded in population since the late 1950’s with those from places east – within Turkey’s borders and beyond – moving to find work to feed their families, to escape the lack of schools and other opportunities, or to avoid actual war.

An increasingly young population, one with sharp divides in how and by whom they’ve been educated. Plus new versions of mismatched immigrants to these shores: refugees, business investors, meanderers like me seeking new cultural immersions, native Turks returning from educations and career starts abroad. All set against a huge flood of tourists and outside ‘western’ cultural influences, connecting Turkey’s residents in actual and virtual worlds. Causing some to emulate other lifestyles, others to cling to their traditions, still more to search for their own combinations.

Raw color in mohair form, tucked away in dusty corners of 16thC hans Istanbul is a marketplace in which all classes and ethnic groups trade. The remnants of a handcrafted past are to be found still within the walls of 16thC bazaars. Traditional materials to be gathered to craft new versions of old skills. Artisans, though few, who work in the old ways, indeed dedicate their lives to preserving them.

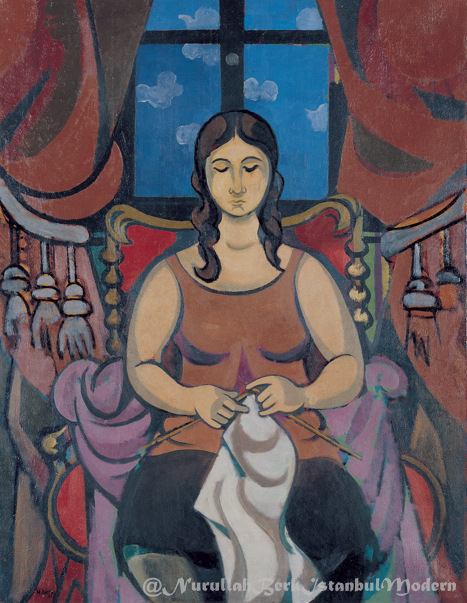

The hand dyed wools to create these handcrafts, whether carpet or handknit I long for a revival of handwork, in this city renowned for its embroidery throughout Europe. Especially during the 16th and 17th centuries in the time of the Kadınlar Saltanatı, the Sultanate of Women, when the Imperial Harem and Valide Sultan were not only patrons of the arts with workshops providing women with work, but virtually ran the Empire.

Early 20thC hand stitched treasures still to be found in the bazaar Embroideries now flood the Grand Bazaar in the Ottoman style, but are hand stitched in Central Asia, where labor is cheap and there is still little work for women other than to stitch or pick cotton and fruit. That women are no longer bound to remain at home by social convention is progress, yet handmaking skills have been lost in the love of the modern, the machine made.

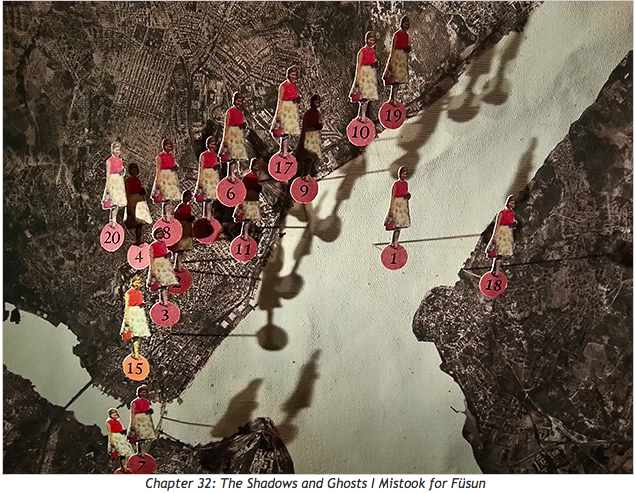

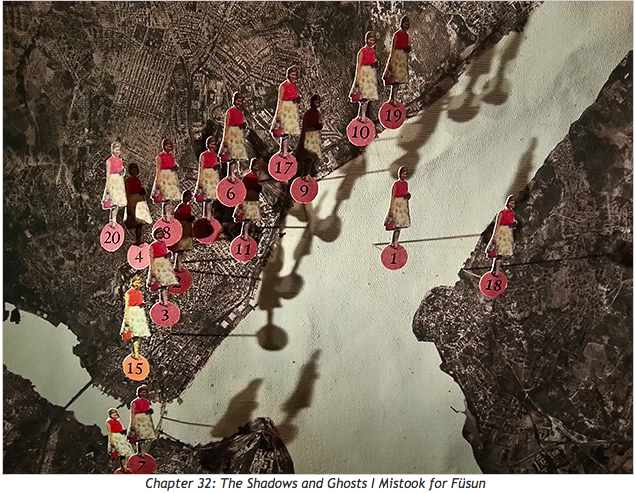

A workshop in which to gather these pieces together, Samatya Those pieces that speak to me document my own personal fiber art culture, with bits from here and there inventing new ways of creative work. Collections of ephemera are all about arrangement and reuse. Like Orhan Pamuk’s Museum of Innocence, an actual gathering of relics compiled by the lovelorn protagonist in his book by the same name, giving us a rarified view of everyday objects illuminating another era of Istanbul life.

Museum of Innocence @Mike Powell 91 Days That vintage version of Istanbul can still be observed around the neighborhoods Galata and Karakoy. Though old warehouses with billion dollar views repurposed to house modern art is progress I can appreciate, how long before too much development and gentrification take over? Late May in Istanbul, we were learning from history along this Bosphorus shore, not realizing that history was about to write a very important page in this city of so much past.

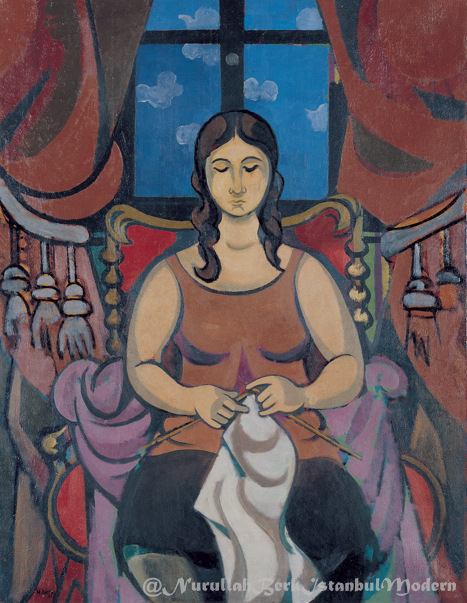

Handmade activities in every Turkish household, Istanbul Modern “My constitutional law is this: I exist if my country and my state exists. We all exist if there is democracy. We must put in our best efforts into strengthening the economy of our country. As our economy strengthens, democracy will take a stronger hold and our credibility in the world will increase“. Vehbi Koc

Visiting icons of decorative art can be overwhelming. It’s easy to fall into the ‘tourist trap’ of taking a million photos, but not really seeing the place while there. I document all the interesting details first, then take time to sit and let them all soak in…as best I can, knowing there are other visitors waiting to do the same!

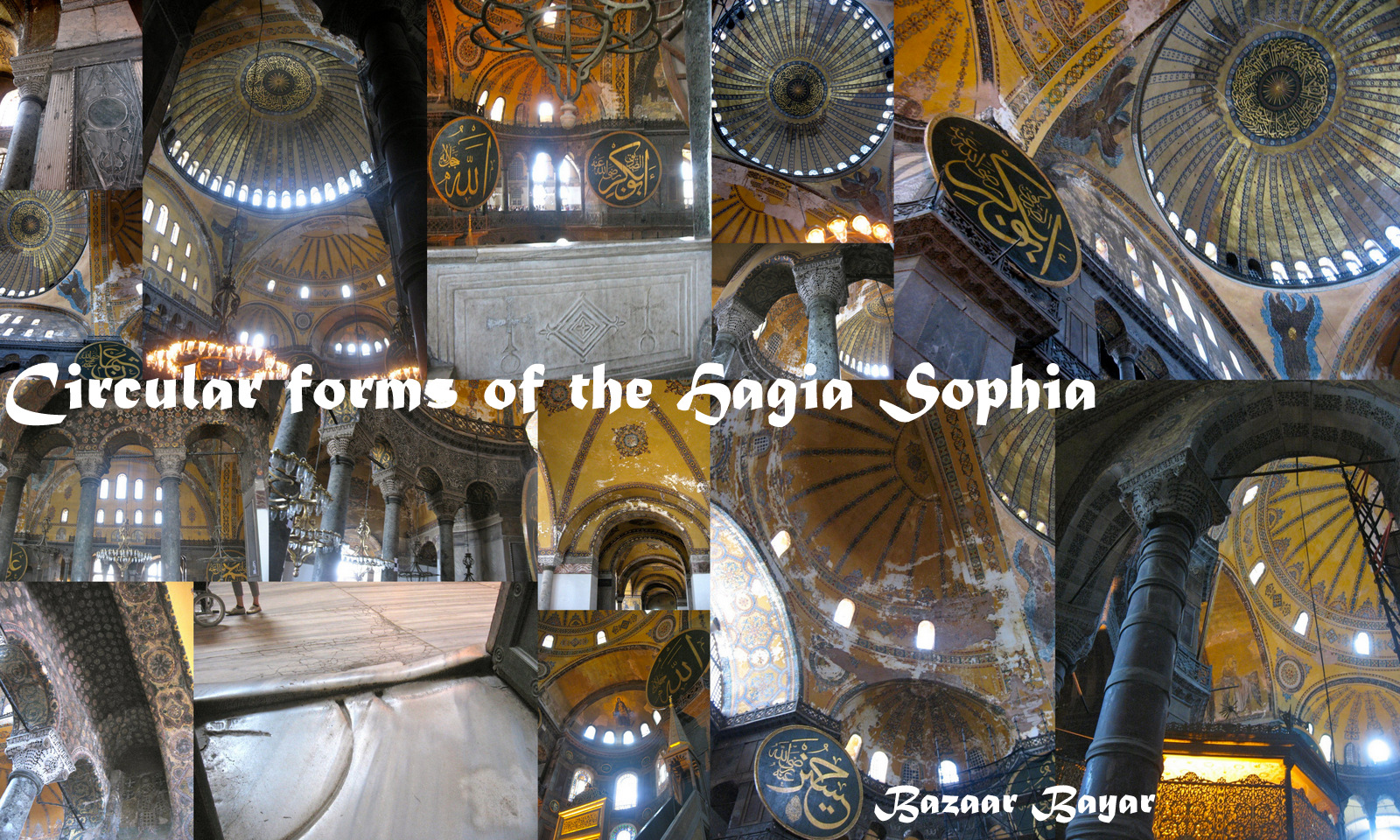

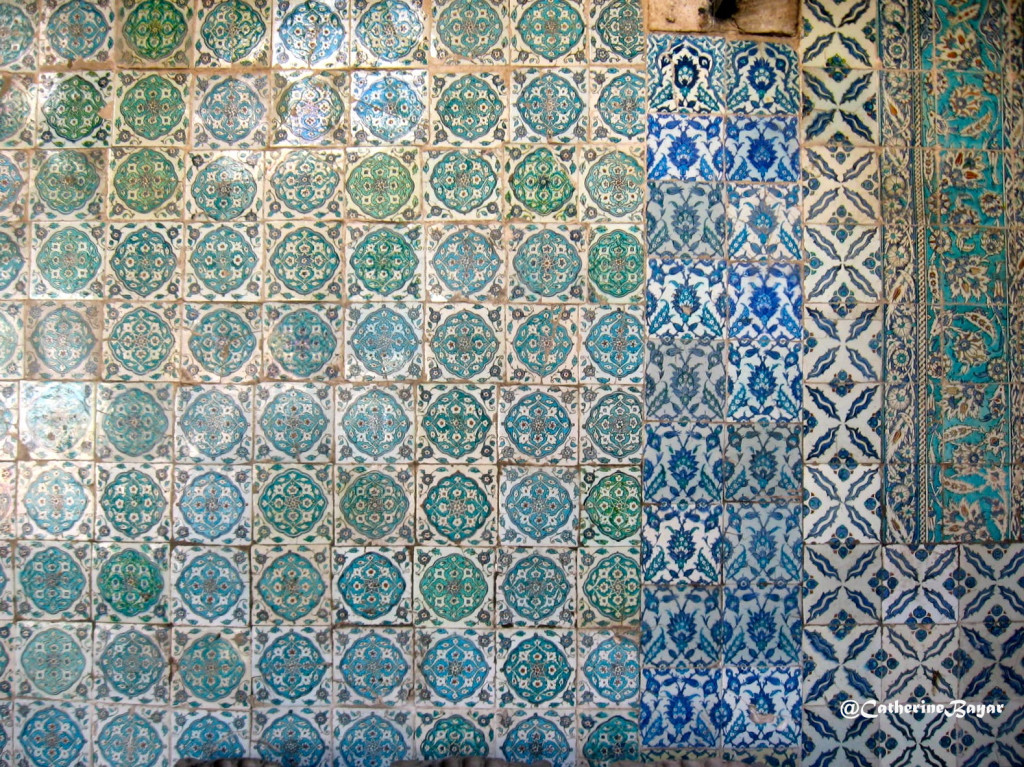

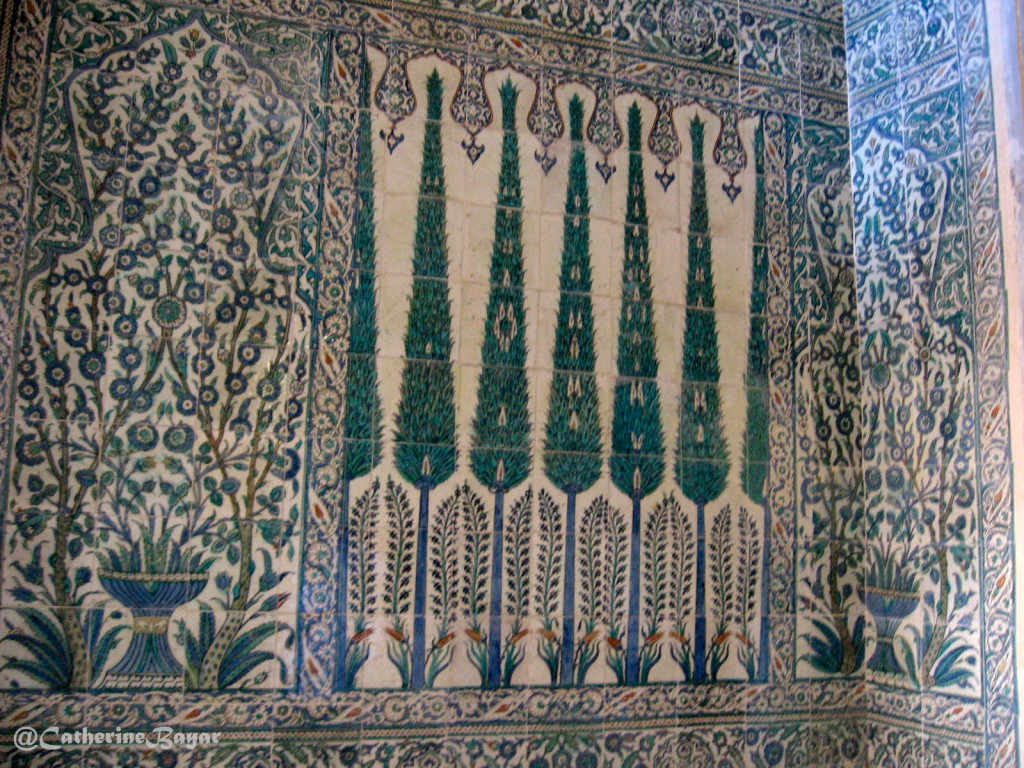

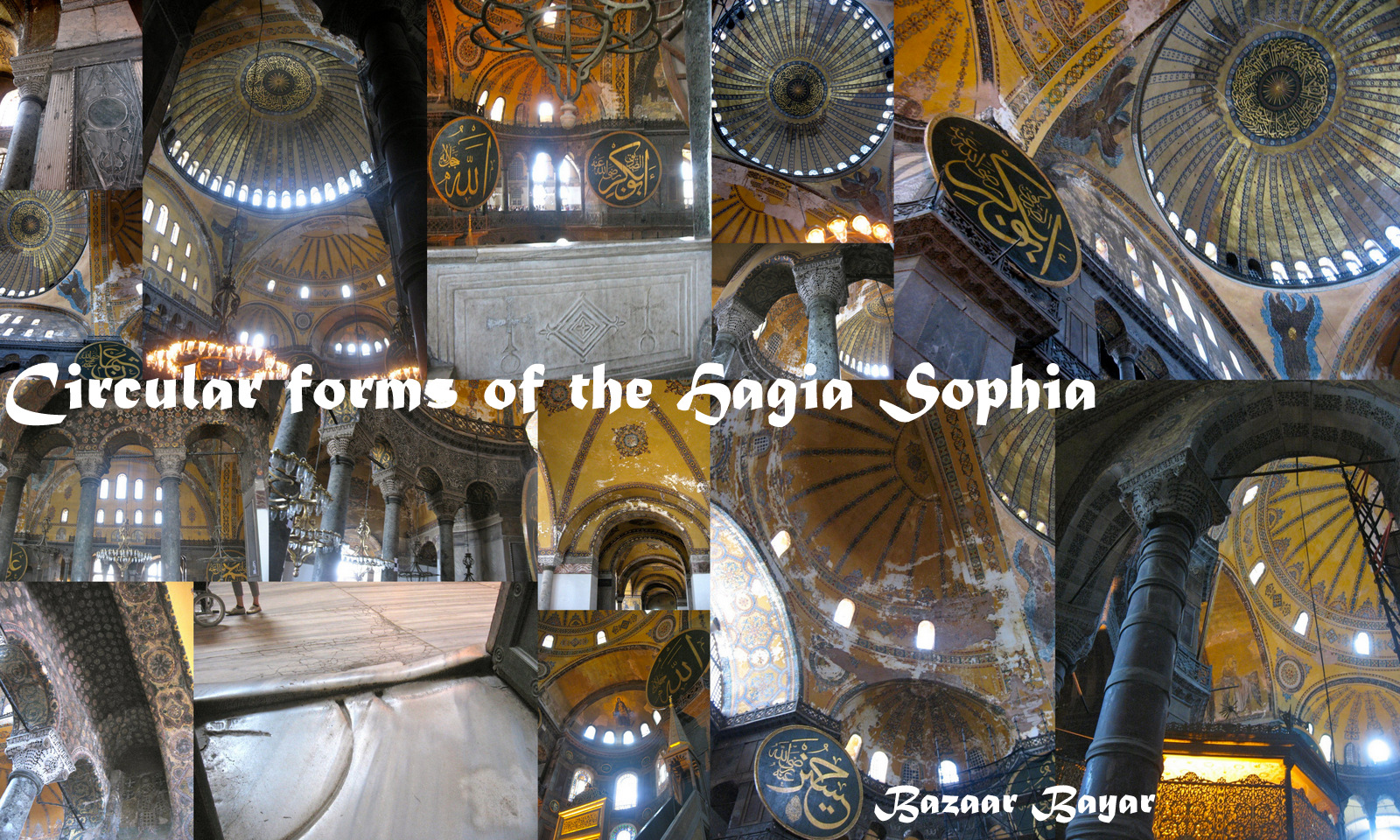

Topkapi Palace Harem Collages are a working tool to help me see and revisit a site again. Easier than scrolling though every last shot, I select my favorites and assemble them roughly in the order of the site layout, if possible. Or I collect all the similar details – the circles, the tilework – and compile those for later inspiration in my design work.

Circular forms of the Hagia Sophia Designers have long used collages, or “mood boards”, before anyone ever thought of creating a site like Pinterest. The point is to compile the visual best of each ‘idea’, whether that idea is a place I’d like to remember, a knitwear collection I’m designing, or a room I want to live in.

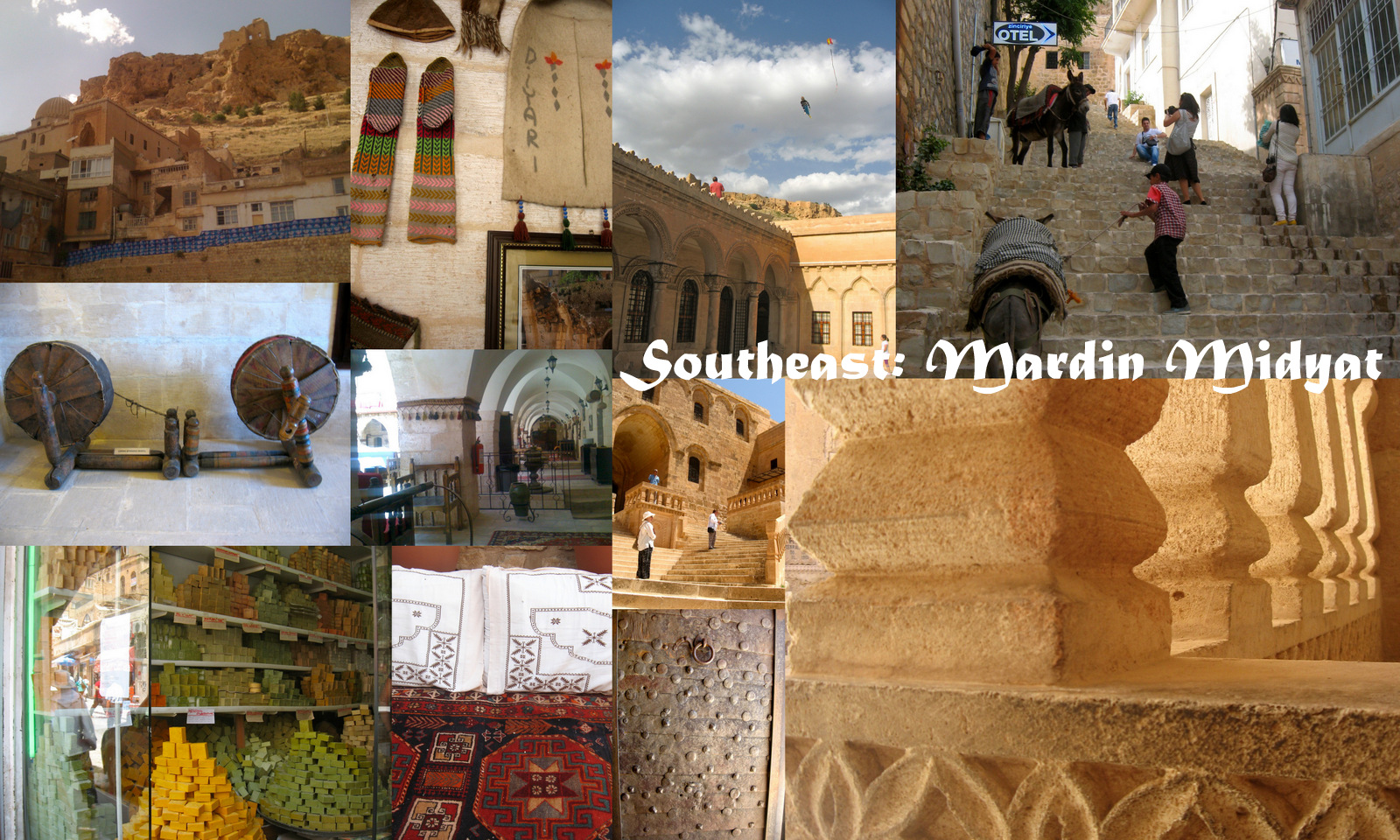

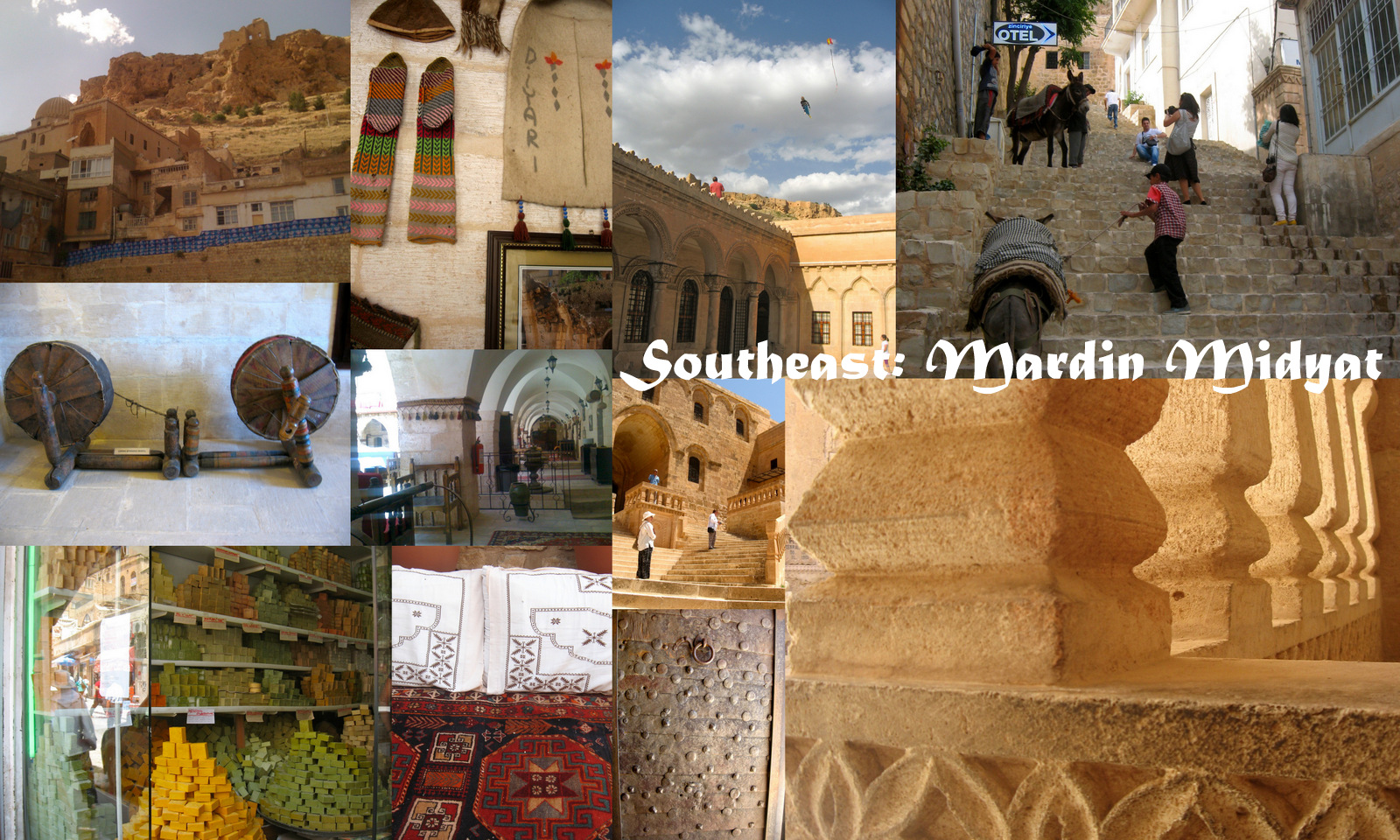

The Southeast: Mardin and Midyat Places have moods; they evoke certain emotions when experienced. When images are gathered together, those feelings return. Like Mardin, as a warm colored, rough-hewn, handmade place.

Or the Aegean region, dominated by blues and whites, formed by the grand cultures of eastern capitals, now in ruin but clearly impressive in their day, and even today.

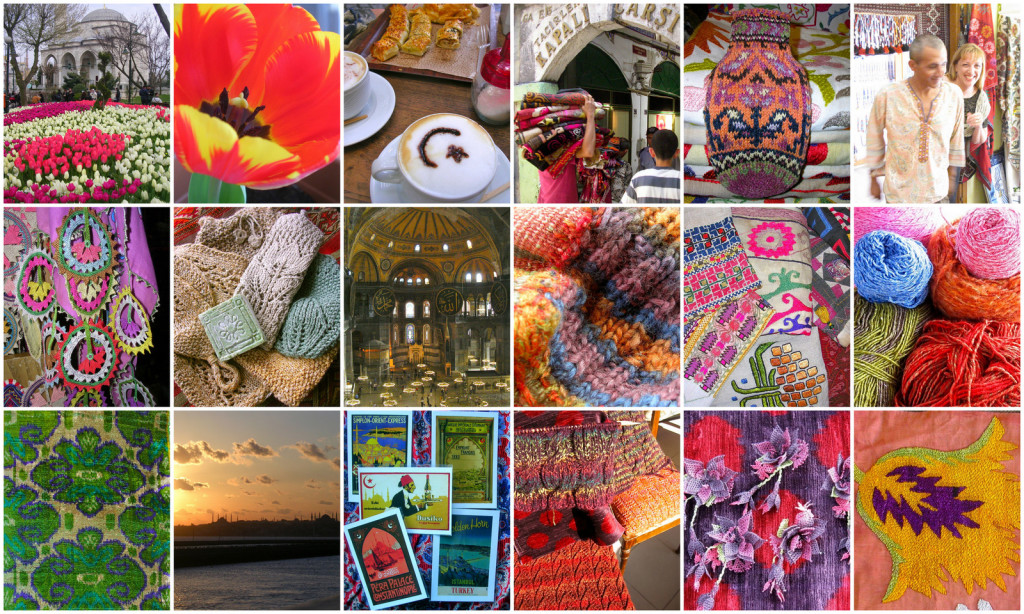

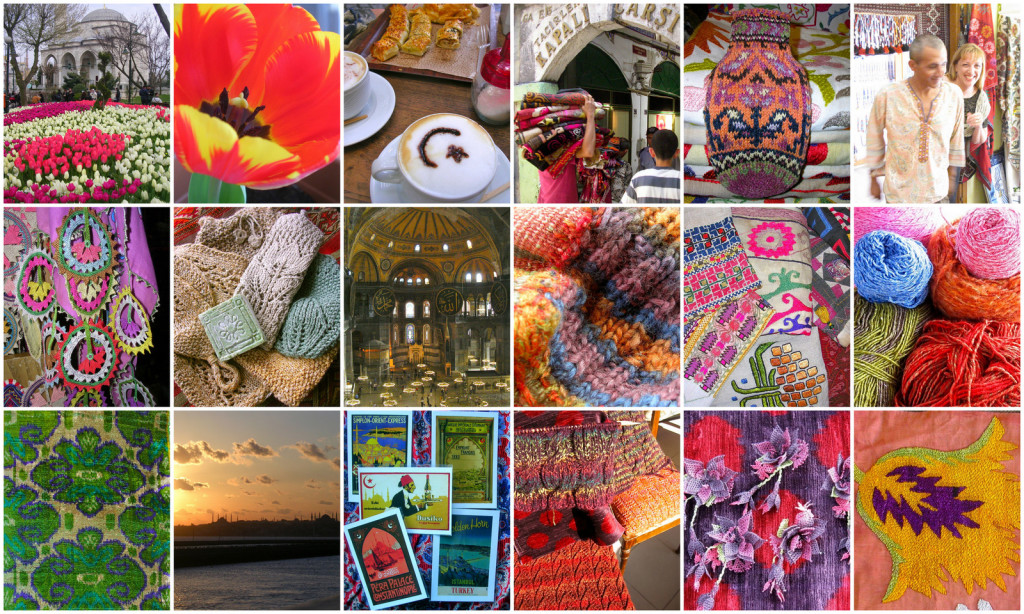

The Turkish Tulip Trip 2013 Collecting images from our entire Tulip Trip, it’d be easy to focus on the handcrafts, forgetting to look at the environment in which they were made. Better to start with the big picture, then revisit each of the colorful kaleidoscope bits, one by one.

Relishing the layers of inspiration in pattern, color and texture of Istanbul’s Greek, Roman, Byzantine and Ottoman past civilizations.

The first of several posts about our spring Turkish Tulip Craft + Culture Trip: Sultanahmet

When Istanbul was green: a mosaic from the Great Palace of Constantinople, royal residence to the Eastern Roman or Byzantine Empire for 800 years. Living in Istanbul’s Old City is a constant reminder of this city’s multi faceted past. As a designer who studies anthropology, architecture, art history and the decorative arts, there are few other places on earth that offer glimpses into Greek, Roman, Byzantine and Ottoman pasts, to be seen in one or two days of frenzied tourism or savored over years of visits. Much of Istanbul is a vast sprawling ode to the modern Turkish Republican era of the last 90 years, with ‘crazy’ construction for the past decade and well into the future rapidly demolishing the likelihood of the city retaining neither its unique character nor its UNESCO World Heritage status. Yet the Old City – defined as the peninsula within Theodosian’s Walls – in particular Sultanahmet, for now remains a living museum, with remnants of Constantinople and Byzantium at every turn.

I’m no historian. I can’t begin to tell the stories of the buildings I so love here adequately enough. But I can share what I see with my visitors, those interested in the cultures that shaped these places. While my chosen pursuit is fiber arts, in particular those made with natural yarns and loops, needles and hooks, most decorative arts in their infinite variety inspire me. What speak to me most are the details, those dots to connect, the elements that link the art of these edifices.

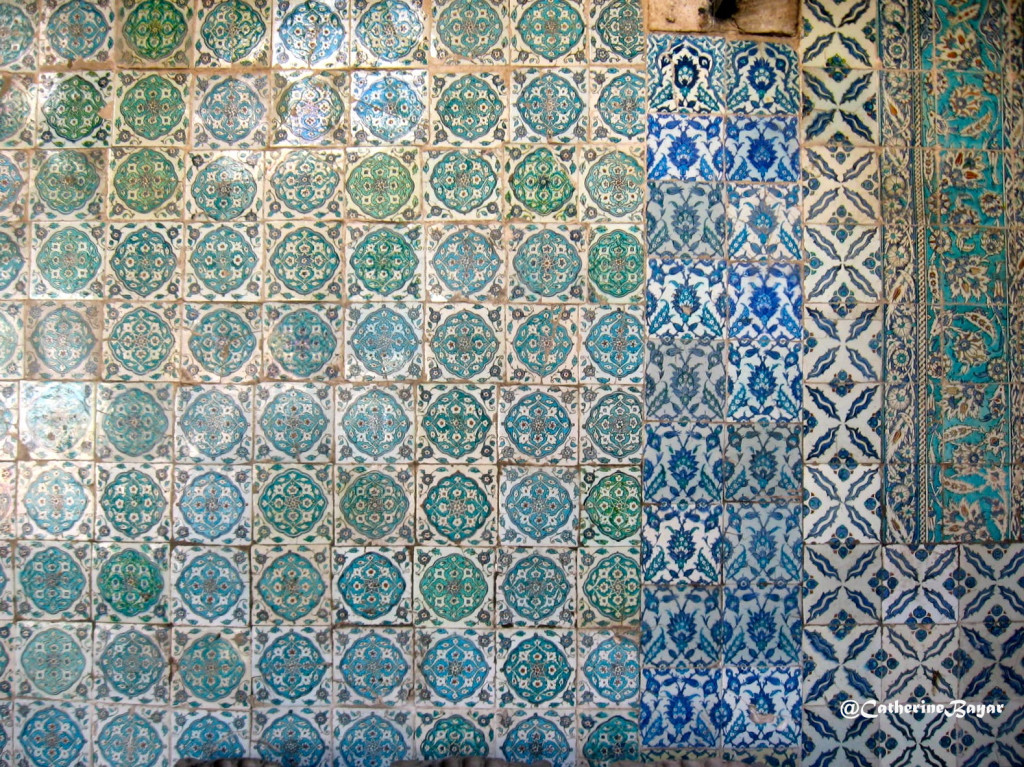

In Istanbul’s Old City, my favorite mosaics morph from depicting natural gods to abstract impressions of pious empresses, to be followed by hand-painted tiles expressing the geometry of nature and sheer joy of pattern and color.

The 6th century main interior dome of the Hagia Sophia, created in Emperor Justinian’s commissioned third church. An innovative structure of half circles on a square, with supportive triangular angel-graced pendentives. The magic of space, creating pendentive domes that changed the history of architecture, with apertures and lanterns to illuminate our spirits, giving us a sense of awe and the divine, no matter what we believe.

Main interior threshold, Hagia Sophia The passage of time on materials like marble, with the tread of a million feet over centuries leaving their mark ever so slowly, yet blending step by step to trace a human path.

Reinforced marble column in a semi-dome, with the illuminated grill of the Sultan’s Loge behind, Hagia Sophia Layers of architecture within the same structure, competing, struggling to survive, yet even metal clasps of reinforcement adding to the rhythm of enduring culture.

Ornate Byzantine capitals on marble columns and original mosaic, Hagia Sophia. The patina of Byzantine tesserae, those small squares of gilt, marble and semi-precious stone, often replaced by painted pattern, but still tucked away in overhead suspension. Swirling capitals with stylized flora adding a lacelike detail to the massive stone columns.

One of several upstairs leaning columns, Hagia Sophia. Grace under pressure resisting change, leaning yet enduring against the ever quickening outside world, trying to keep the silence within.

Upper gallery with Deësis mosaic in the background, Hagia Sophia. The repetitive form of the arch, connecting past to future, a Roman invention allowing repetitions of form in arcades and vaults. Ornamented with floral ribs and motifs floating on sharp color.

Remnants of crosses which once ringed the upper gallery, with hand wrought iron chandeliers and a 19th century calligraphy medallion, Hagia Sophia. The overlap of religions, rarely peaceful as places of worship change hands, but coexisting to encompass all. Sharing the universal sense of the traditional in progression to the contemporary, yet transcending time.

Simple carved crosses, Hagia Sophia.

Discovering the remnants, the tiny bits left scattered by anonymous hands, rarely noticed. The conversation between formal arts and the need for individual expression.

Circular forms in endless variety, Hagia Sophia. And always the circle, this form which connects with no beginning, no end. Joining cultures, linking elements to represent the eternal.

interior Courtyard of the Favorites, Topkapi Palace Harem. These layers and forms continue nearby, with structures built by successive sultans of the Ottoman Empire, leaving their mark in much the same way as the emperors before them.

Carved walnut, inlaid mother of pearl and ornate pierced brass cupboard door woodwork, Topkapi Palace Harem. The details of artistry, craftspeople who worked ceaselessly and anonymously to create intricate works of art, often taking years to finish a single piece.

Stained glass, tiled and carpeted corner of the Şehzade (Crown Prince) Kiosk, Topkapi Palace Harem. The intimate interiors, offering privacy while flooded with afternoon sun, bringing hand-painted ceramic and hand-knotted gardens inside while offering the comfort of an embellished cushion and a warming brazier.

Interior Sultan’s corridor wall and ceiling, Topkapi Palace Harem. The riotous combinations of pattern and color. Here the layers transform a curved corridor wall into a physical tearsheet of detail depicting Ottoman style.

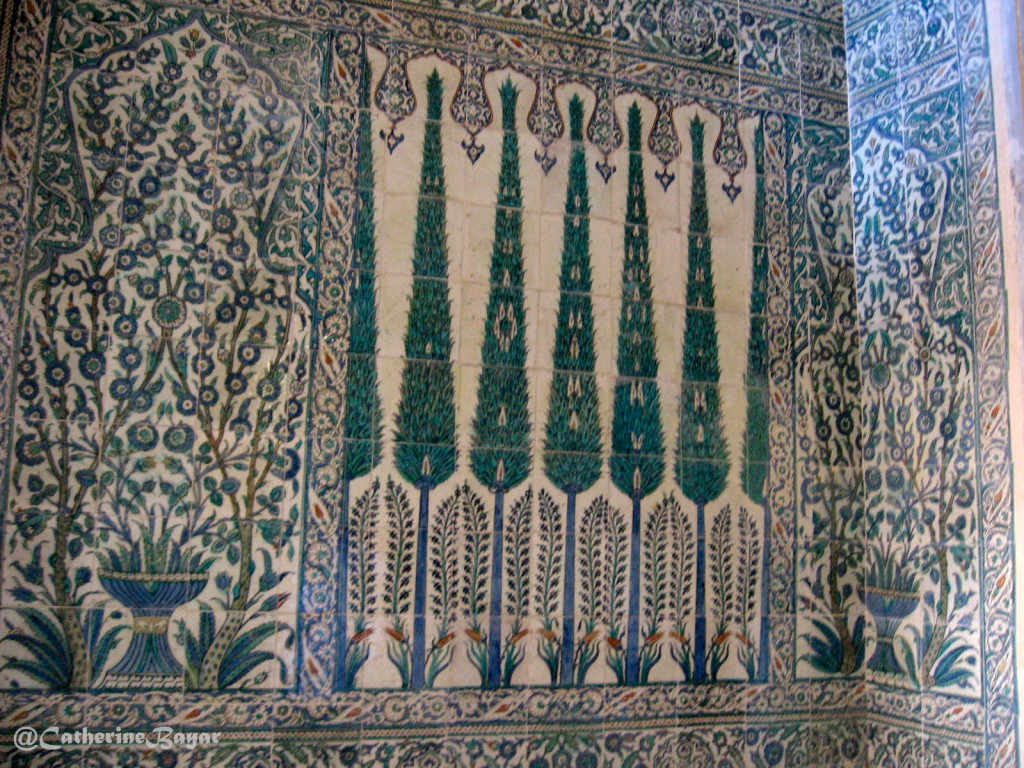

Tiles spanning the pinnacle of the Ottoman Empire, Topkapi Palace Harem. Nature depicted in her myriad geometric forms. And like nature, unconcerned with symmetry in the overall composition. The colors: deep blues and turquoises, the coral reds and rich greens, against the airy space of a white ground. An infinite variety of tulips and carnations, representing a paradise on earth.

Courtyard of the Eunuchs at the entrance, Topkapi Palace Harem. These historic buildings may be constructed of stone and glass, decorated with mosaic and tile, but elements of whimsy and inspiration prevail. A power ranging from playfulness to the divine, a wealth of ornamented environments that provides lessons on design, no matter the craft.

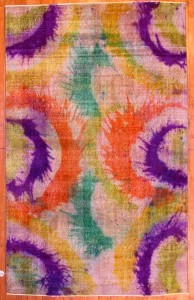

The Turkish Tulip: Fiber Arts + Culture Trip.

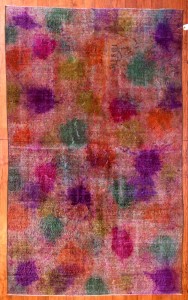

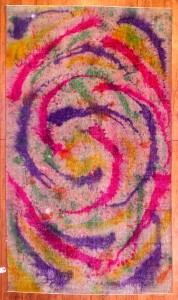

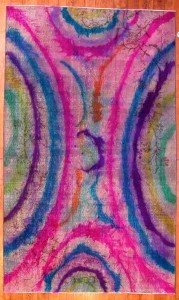

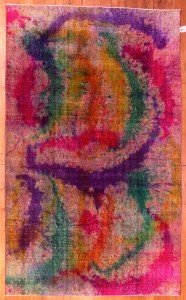

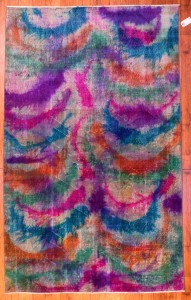

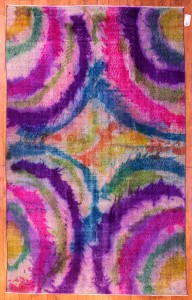

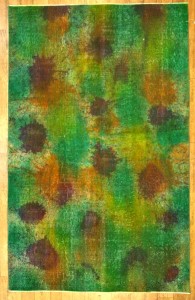

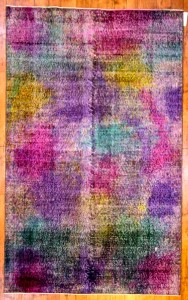

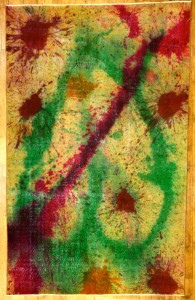

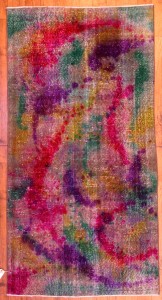

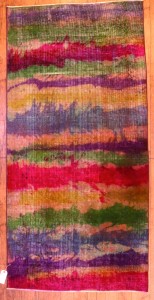

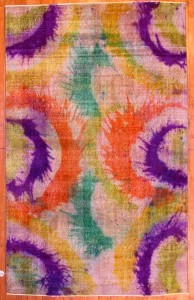

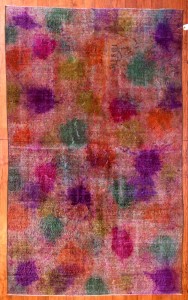

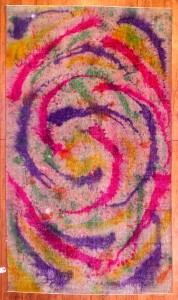

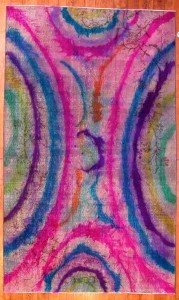

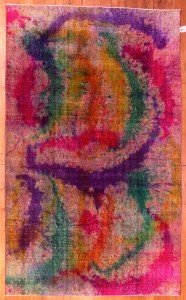

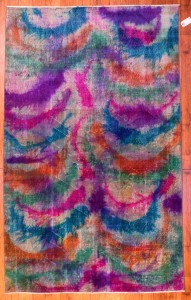

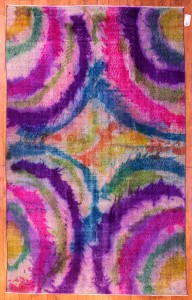

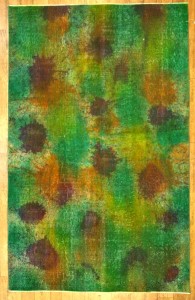

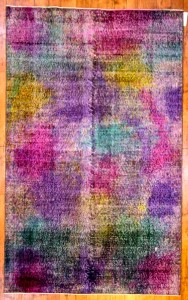

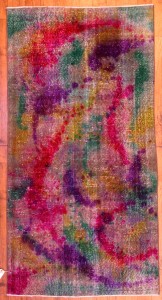

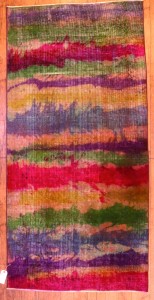

Original, bright, full of motion and vibrant color!

Want one of these revitalized carpets? Contact us here.

8’7″ x 5’7″ (2.62 x 1.70)

$1985  8’2″ x 5’1″ (2.50 x 1.56)

$1750  8’2″ x 4’9″ (2.50 x 1.45)

$1650  7’9″ x 4’11” (2.37 x 1.50)

$1585  7’11” x 4’9″ (2.42 x 1.46)

$1585  7’10” x 4’9″ (2.38 x 1.46)

$1550  7’10” x 4’9″ (2.38 x 1.46)

$1585  7’8″ x 4’9″ (2.34 x 1.46)

$1550  7’8″ x 4’10” (2.33 x 1.48)

$1485  7’6″ x 4’11” (2.28 x 1.50)

$1485  7’8″ x 4’9″ (2.33 x 1.46)

$1550  7’5″ x 4’9″ (2.27 x 1.44)

$1485  6’7″ x 3’8″ (2.00 x 1.12)

$950  6’7″ x 3’6″ (2.00 x 1.07)

$950

6’7″ x 3’3″ (2.00 x 1.00)

$950  7’10” x 4’11” (2.40 x 1.50)

$1585

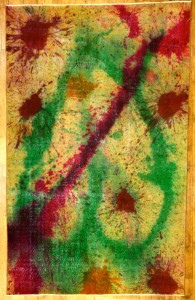

Some projects need few words. Strange for me, one who loves to talk and write. But the artistry of Theresa May-O’Brien of Ikonium Studios in manifesting amazing colors and patterns in her work often leaves me speechless (quite the accomplishment).

So when she asked me to ‘fix’ a jacket body that was a little too small, I happily added some elements, knitted in Ikonium’s hand dyed silks of course, with a little linen yarn here and there, to blend the colors of the knitting like she did with the wool. I had so much fun, I barely noticed the warmth of that thin but compact wool as I worked on our now steamy terrace.

After we complete a few more garments for summer and fall, each quite distinct from the last, I’m feeling the urge to upholster. More to come…!

With tulip leaves on our terrace well up, spring is on its way early here in unseasonably mild Istanbul. We are anticipating our May journey. Turkey has been in global news for some serious reasons already in this New Year, so it’s time for an update!

Closest to home, the disappearance and murder of Sarai Sierra has shocked us all. Travelers simply don’t go missing here often. The country’s reaction ranges from earnest discussion to rampant rumormongering, in this nation that loves dreaming up conspiracy. As a longtime solo female traveler to about 45 countries, 14 years living here, with 3 of those in the Old City center of Fatih Istanbul, Turkey remains by far one of the safest places I’ve experienced. The concern about this recent event only confirms it will become more secure.

Also in the news, the bombing of the US Embassy in Ankara by a leftist group with loose Russia/Syria ties protesting Turkey/US/NATO relations, as Patriot missiles are installed along the southern Turkish border. Again, Turks are analyzing the details, but past increased security has proven a deterrent to greater death and damage.

The tragedy in Syria continues, but relatives and friends along our route report no major change to their lives, other than an outpouring of charity and help for Syrian refugees in the border area well west of where we’ll travel. The ancient city of Hasankeyf has been saved for now with a dam halted by court order. But work seems to be proceeding anyway, so we’re glad to get there again this year.

What do we conclude from these events? What we know to be true: Turkey is not a scary place. It’s ever changing, creative, colorful country full of wonderful people who want to share their homes, their art, their culture with you. We invite your questions and suggestions about our journey. We look forward to showing you our world this May!

Welcome 2013!

|

|