|

|

Photo: Theresa May Obrien Photo: Theresa May Obrien

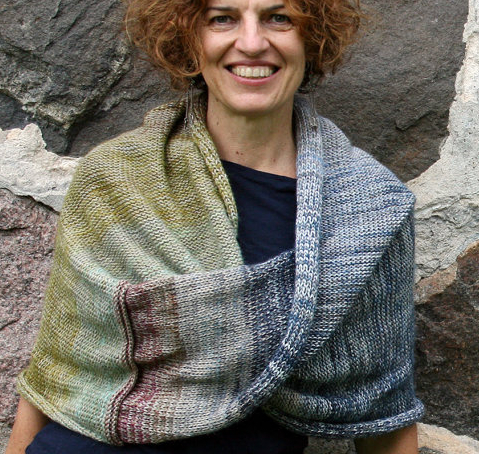

We’ve been on a rollercoaster ride here in my beloved city of Istanbul. A chaotic life has left me scattered, unable to write much, only make. But recently, an international women’s group asked me to reflect on the intersections of craft and culture, globalization and activism I’ve experienced in my 20 years plus in Turkey. And so, I begin to write again.

The last few years have been challenging: for Americans and Turks, for Istanbul expats and locals, and globally, for women. Two decades observing the ebb and flow of Turkish tourism, the seismic swings of the political pendulum in Turkey – and in the US —have been a rollercoaster ride of the unexpected and unprecedented.

Photo: Guy Lamontagne Photo: Guy Lamontagne

But as things play out on the macro stage, I also see a quiet handmade revolution unfolding. I see women knitting pussy hats in political protest, undercutting fast fashion with slow making, and challenging us-versus-them narratives with the simple act of gathering with other women to talk, laugh and create.

Against this turbulent backdrop, I feel like I’ve come full circle. I first visited Istanbul in the early ‘90s, while working as a design director for a big California-based clothing manufacturer, looking for quality cotton t-shirts at a cheap price. Fast fashion had yet to take hold of the industry, but department stores were pushing suppliers to provide merchandise at a price to compete with more direct lines of production, like the GAP.

At that time I worked in about 40 countries but unlike most, Turkey was more pleasure than drudgery, with competent professionals who also took incredible care to showcase their country to us visitors. They urged me to see more than just its most famous megacity, so after many work visits, I took a month long solo tour in 1998. I had been contemplating relocation to a country in the Mediterranean region but was most definitely not looking for a romantic relationship. Kismet had other plans of course, and placed a carpet-selling, textile-hunting man in my path. Smitten, we moved in together, with surprisingly no objection from his relatively conservative Muslim family. We married four years later and settled in Selçuk, a lovely Aegean town filled with Greco-Roman and Byzantine ruins, tourists and 30,000 inhabitants.

Photo: Guy Lamontagne Photo: Guy Lamontagne

There were other expats around but I hadn’t moved to Turkey to cling to my culturally American quirks and remain an outsider. But until I learned Turkish and Kurdish, how could I connect with my many new female, headscarf-wearing relatives, none of whom spoke English? They were all wonderful home keepers and cooks, baking their own bread, making every meal from scratch using nothing store-bought, skills I appreciated but had no time with a new business: a kilim and carpet shop in the center of town and, later, a café and wine bar called Mosaik.

Needles and yarn were things I always had time for, a favorite talent and compulsion for keeping my hands and mind busy while I grappled with fitting with family who accepted me, but had grown up in such a different culture than mine. Yet one fact struck me: every woman in our household was a knitter. Knitting was a lifeline I grabbed with gusto.

My mom and grandmother had shown me how to knit as a child, but I’m left-handed, so their English style instruction didn’t stick. In my 20s, I picked up the needles again, this time in Denmark on a trip with my knitwear design mentor. His non-English-speaking mom showed me how to take the luscious handspun wool available everywhere and knit Continental style, which suited my ambidextrous tendencies perfectly.

I couldn’t yet tell my new relatives much about myself, but I could show them me. How I put together colors and patterns by making a hat for a nephew, how I played with scale and texture in a dress for a niece. In turn, they showed me how they knit intricate multi-needle jacquard slippers that kept our feet so warm. We dreamed up hats, scarves and socks to sell in our vintage textile shop. At the time, cruise ship travelers rarely got beyond the high-pressure shops of the port town Kuşadası, so Selçuk got a quirky mix of academics and backpackers. But that suited me fine, trading travel stories and tales of Turkish daily life in our shop by day and café by night. If shoppers weren’t interested in hand woven kilims and carpets, they’d snap up our hand knits instead.

But these women didn’t just knit. They excelled in a variety of traditional Turkish crafts. They embroidered towels, crocheted bath scrubbers and oya, the decorative floral trim that adorned their headscarves, painted ceramics and wet-felted small rugs.

They no longer had time for weaving large projects like they did when my mother-in-law was a girl, when women gathered after the farming, cooking and other house chores were complete, to show their daughters how to make the items they would need for their dowry. As Turkey has modernized, the ease of buying mass-produced goods has increased.

None of my husband’s six sisters needed to learn to weave. It was far more affordable and far less time consuming to buy from the big box stores cropping up all over Izmir province. People preferred machine made, synthetic fiber rugs for ‘easy care’ to the painstakingly woven carpets that took months to create. The only women in our town still weaving in traditional wool, silk and cotton worked for “carpet villages”, commercialized stops for the bus tour groups to demonstrate traditional Turkish fiber crafts. These weavers were paid a daily rate and insurance benefits, but the weaving they did was mainly for show. But clearly the women of our town retained the timeless urge to create beautiful things by hand, if on a smaller scale than their mothers and grandmothers.

Tourism had turned weaving into a commodity that had to compete with global pricing, so the most of the goods actually sold were predominately made in cheaper labor countries farther to the east. That wasn’t its only effect: As tour group visits became restricted by town halls competing for gate fees, small businesses like ours struggled, a main reason we decided to move to Sultanahmet in 2010.

Though Istanbul was a huge place, we both felt firmly at home in the maze of the bazaar district. In contrast to my ‘90s visits, I could see those imported mass-produced items overtaking Turkish culture, especially in the fiber trades.

Where streets had traditionally been arranged by product sold—one lane for scarves, another for slippers—shops now displayed the same Chinese made products. When admiring a sparkling hand woven silk, a shop owner would woo me with tales of weavers in small Anatolian villages, and feign indignation when I told him I knew the saris had been woven in India. The number of textile shops and carpet wholesalers I trust to have Turkish goods, and those with authentic vintage and antique weavings and embroideries, has dwindled considerably.

In this world-class city, I missed the exchange I had with the women of our former small town, so I joined a venture to showcase Turkish products, and started new dialogues. I see craft as a tool of economic empowerment but also a subtle tool of education, particularly for travelers flocking to Istanbul in the early 2010’s when Istanbul was a European Culture Capital.

Visitors were especially curious about the perceived “Islamisation” of this country. As I helped visitors navigate the narrow lanes of the bazaars, I was often the only native English speaker they met during their trip to Turkey. They showered me with questions, especially about women’s roles and customs.

We’ve hosted knit retreats for artisan travelers who have come to see historical sites and experience another culture hands-on, through shared sessions of knitting, crochet, embroidery and wet felting. We’ve also traveled with groups beyond our Old City walls to Mardin, my husband’s birthplace, and back to Selçuk, bringing a culturally diverse range of Turkish women and textile intrigued foreigners together so they can communicate directly themselves.

Watercolor: Maracuja Project Watercolor: Maracuja Project

But I didn’t want our dialogue to involve only tourists to Turkey. In 2014, as the flow of tourists began to slow as a result of protests and damaging media coverage, I started a Facebook group Handmade Istanbul, to connect with other craftivists of Istanbul, whether native born or foreigners like me. I’ve been dismayed at the number of traditional artisans struggling to survive—particularly women who relocated to Istanbul from rural Anatolia so their men could find work, or refugees escaping war along our border—but heartened to meet educated Istanbullular savvy enough to sell their handcrafted goods online. I wanted to offer these artisans the opportunity to earn through their crafting skills. Handmade Istanbul’s seasonal markets are in part a response to this, in that they raise visibility of traditional and contemporary local artisans and provide an opportunity to sell.

In 2017, we eternal optimists recover from the rollercoaster ride of the past several years and patiently wait for tourists to return to Sultanahmet. We offer workshops in our streetside garden shop just south of the Cemberlitaş tram stop, to examine various traditional handcrafts, with the goals of reinterpreting them into modern uses, and to use craft to raise awareness of social issues. We also host Stitch ‘n Bitch meetups most Sunday afternoons, with a wide variety of small handmade projects, fiber or otherwise, shared and admired.

We may not speak the same languages, but we do share a common language of craft. I’m fascinated to hear what conversations develop in our gatherings. Designing new ideas from the old to establish a financially viable cottage industry is challenging – that’s the entrepreneur in me. But I’m also a writer. Of equal importance is documenting the environment in which we share our stories over busy hands and steaming cups of tea, creating a place for bridging cultures, discovering the universal characteristics that compel us to create.

The above article appears in the July/August 2017 issue of LALE magazine, for the International Women of Istanbul. An earlier version of this article was published by Hand/Eye Magazine in October 2010. With contributions from LALE Deputy Editor Ruth Terry.

Find Bazaar Bayar and Handmade Istanbul on Facebook

Save

Save

Save

Home decor for lively spaces: an up-close look at handmade fiber art that brightens any space.

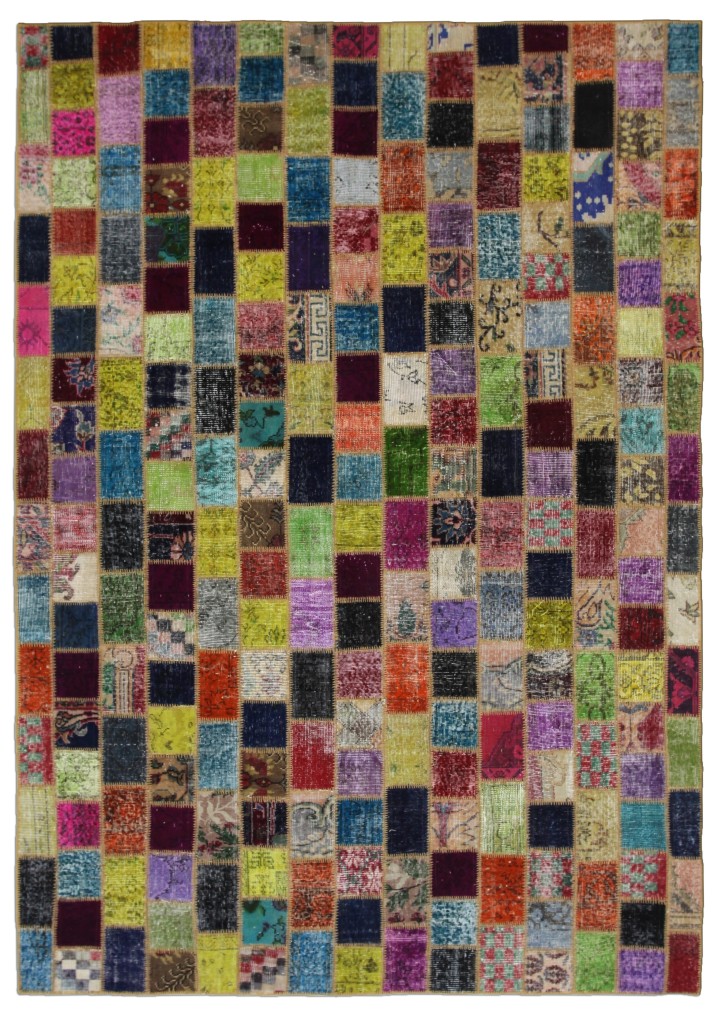

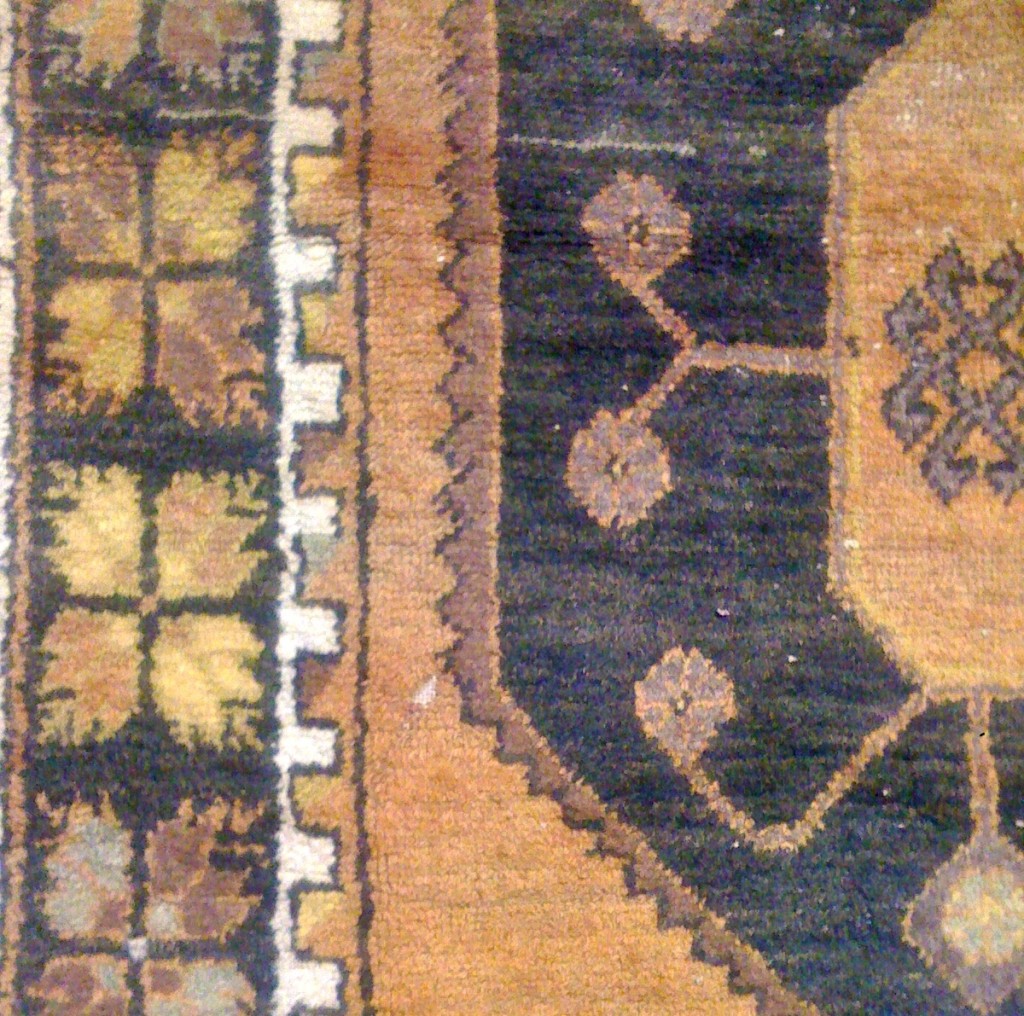

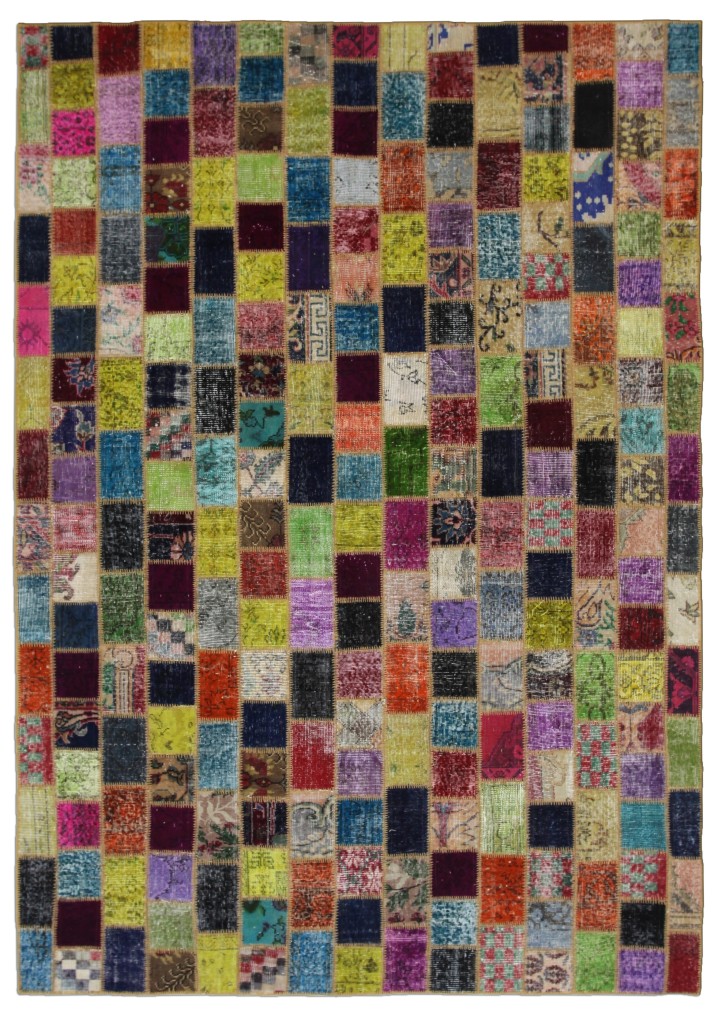

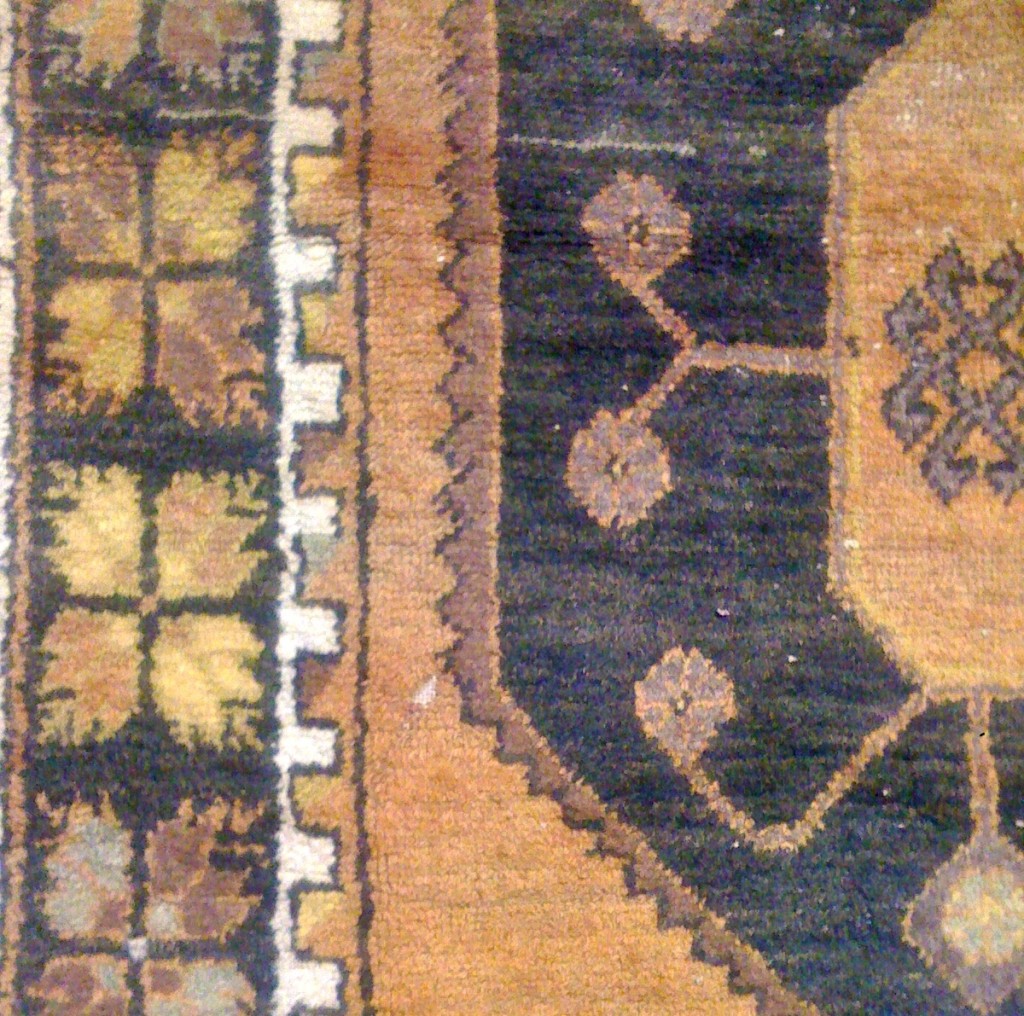

Blending and clashing like fields of tulips just burst from the ground, design is often the challenging act of reflecting Mother Nature in spinning yarns and combining colors. Whether random slashes like this ‘old wool’ kilim, or tidy patches like this mosaic patchwork carpet, bringing the look of spring inside makes us happy, whatever time of year it may be.

Add a cozy tulip throw hand knit in orderly rows, in Wrapture by Inese’s anything-but-ordinary mohair, cotton and silk windings, custom made for Bazaar Bayar. Lively color we love to live with, for any room of a home.

The season has changed here in Istanbul, overnight it seems, with dramatic thunderstorms and much needed monsoon rains. Suddenly, time to put away the sandals and summer dresses and bring on the boots and leggings. And a soft warm throw to ward against the chill evening breeze…

Write as I might, it’s best to show the first pieces of our new collection of home decor – handknit in luscious yarn courtesy of Wrapture by Inese – with our overdyed rugs and old wool kilims. Colors and textures galore! Click on each pic below for more info…

A craft workshop in which to gather these pieces together, Bazaar Bayar Samatya Time for our winter hibernation to come to an end. There is just too much craft inspiration swirling around us, despite grey days and endless revelations worthy of the most outrageous soap opera in local and national political news.

Ready to leave the crazy news aside and be inspired as well? This recent Time Out Istanbul article compiles a host of wonderful places to be active in Istanbul in 2014, including our Bazaar Bayar. We “self-proclaimed color and fiber junkies” would like to invite you to let us know what workshops you’re interested in attending, and when! We’ll have more solid times posted soon, but meanwhile your input helps us come up with the best schedule for most.

Also, if you’re an artisan/crafter/artist/creativity fanatic living in the greater Istanbul area, join us in our newly created Facebook page, Handmade Istanbul. A place to share your work and get it seen in a closed group of like-minded local folk. We do limit membership to keep out the mass-produced riff raff. But pics of your work can be shared by members outside the group, hopefully to bring you local interest and sales, if that’s your desire. Join us!

It’s my birthday today. I’ll be spending it taking pics of a color-drenched collection of vintage and antique carpets we’ve just received from a friend here in Sultanahmet who has decided to retire, closing his shop. We are so inspired to be living with these handwoven treasures for a time, and will be slowly sharing each of them here and in our Etsy shop.

Check back soon! Better yet, come visit us if you happen to be in Istanbul…

“I tell my customers – I am addicted to playing with colors, thank you for supporting my habit.” “I tell my customers – I am addicted to playing with colors, thank you for supporting my habit.”

I met fellow color and fiber junkie Inese Liepina through a mutual designer friend in San Francisco, who introduced us via email on my birthday in 2010. Inese, raised in Chicago by parents who escaped Latvia in WWII, returned to her family’s roots in Riga, relaunching her knitwear business Wrapture by Inese during tough economic times. Unhappy about paying high prices for Turkish kid mohair sold to Italian mills and marked up significantly for sale in the EU, she decided to come directly to the source, here in Istanbul.

I’m grateful that she did.

It took just one visit to our local yarn han to see that we were kindred spirits. Anyone not as enraptured with fiber and color might be puzzled at the sight of us digging through dusty bins of yarn on spools, gathering the best hues and softest feels into a huge pile, wheeling and dealing with the merchants for tens of kilos at a time. Not just one red, one yellow, one blue, one green…but every incremental shade, compiling a tactile rainbow in full blown color. It took just one visit to our local yarn han to see that we were kindred spirits. Anyone not as enraptured with fiber and color might be puzzled at the sight of us digging through dusty bins of yarn on spools, gathering the best hues and softest feels into a huge pile, wheeling and dealing with the merchants for tens of kilos at a time. Not just one red, one yellow, one blue, one green…but every incremental shade, compiling a tactile rainbow in full blown color.

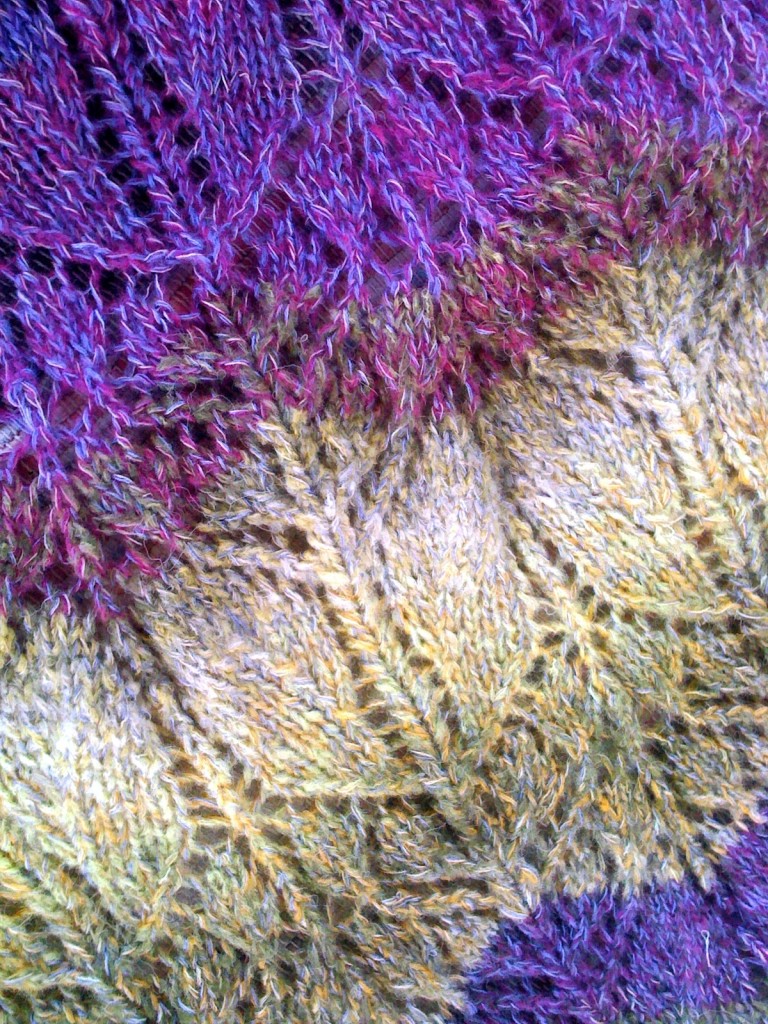

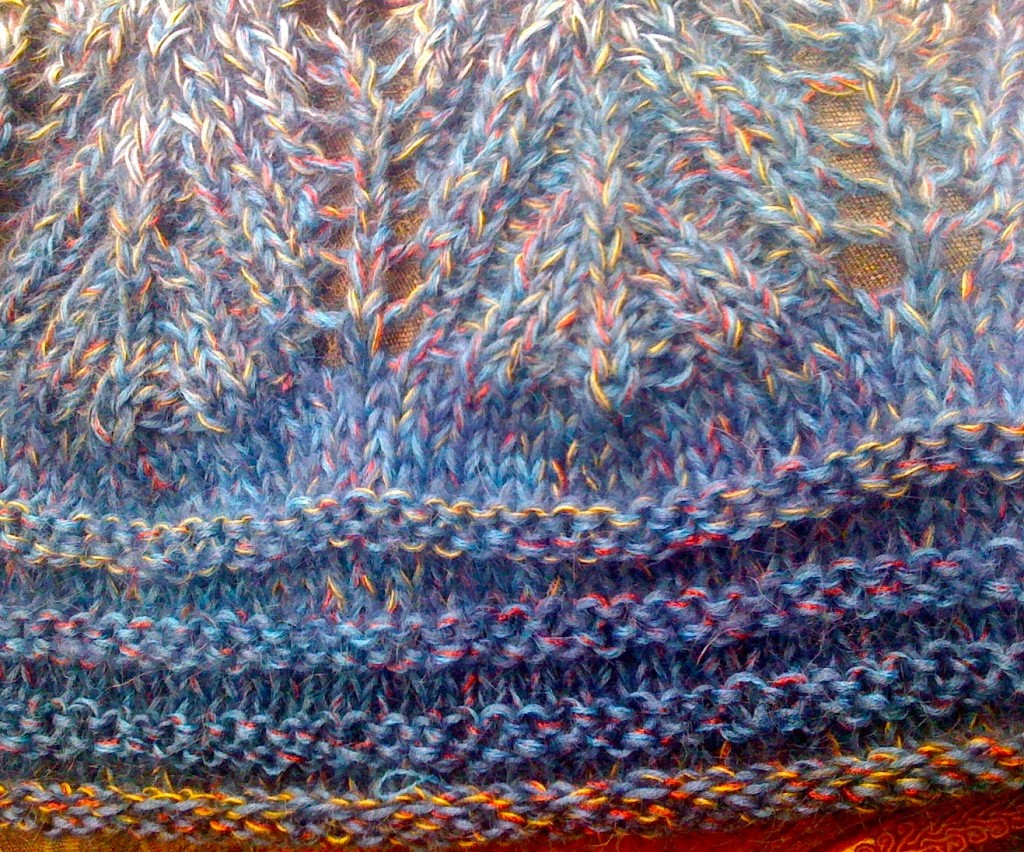

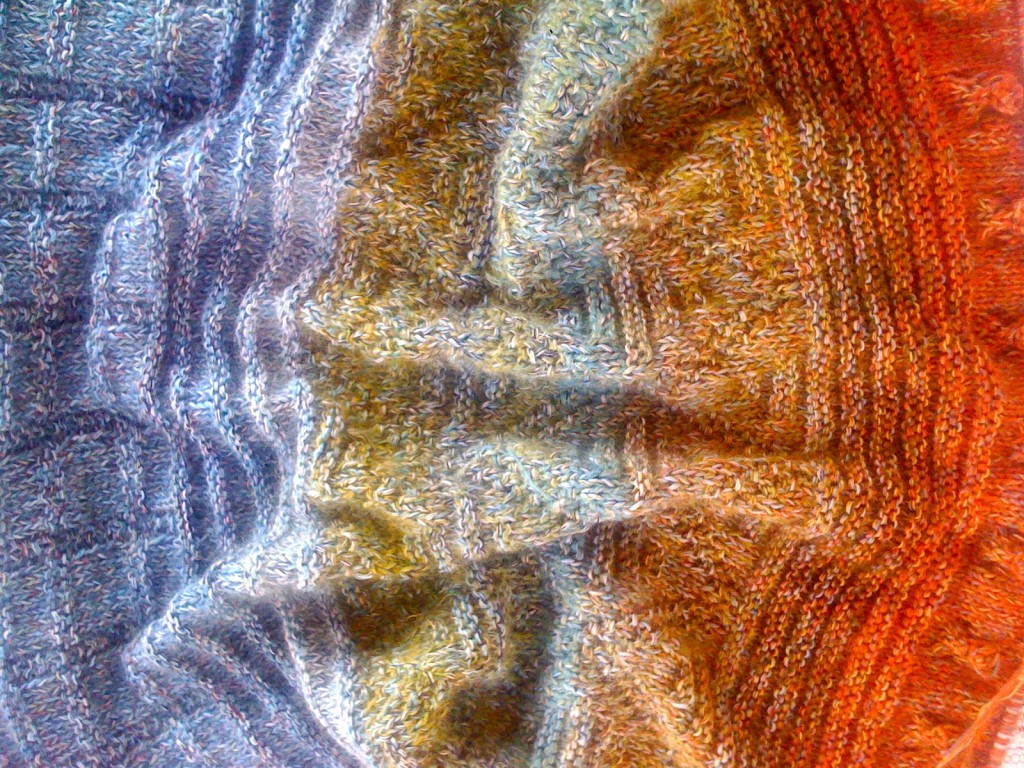

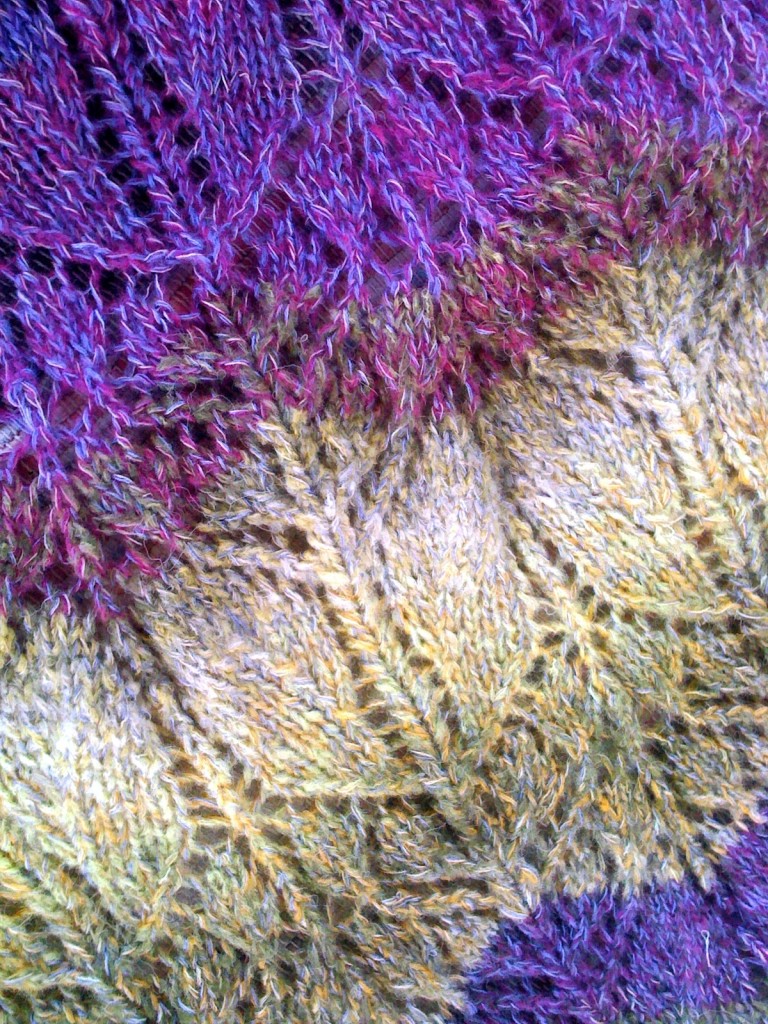

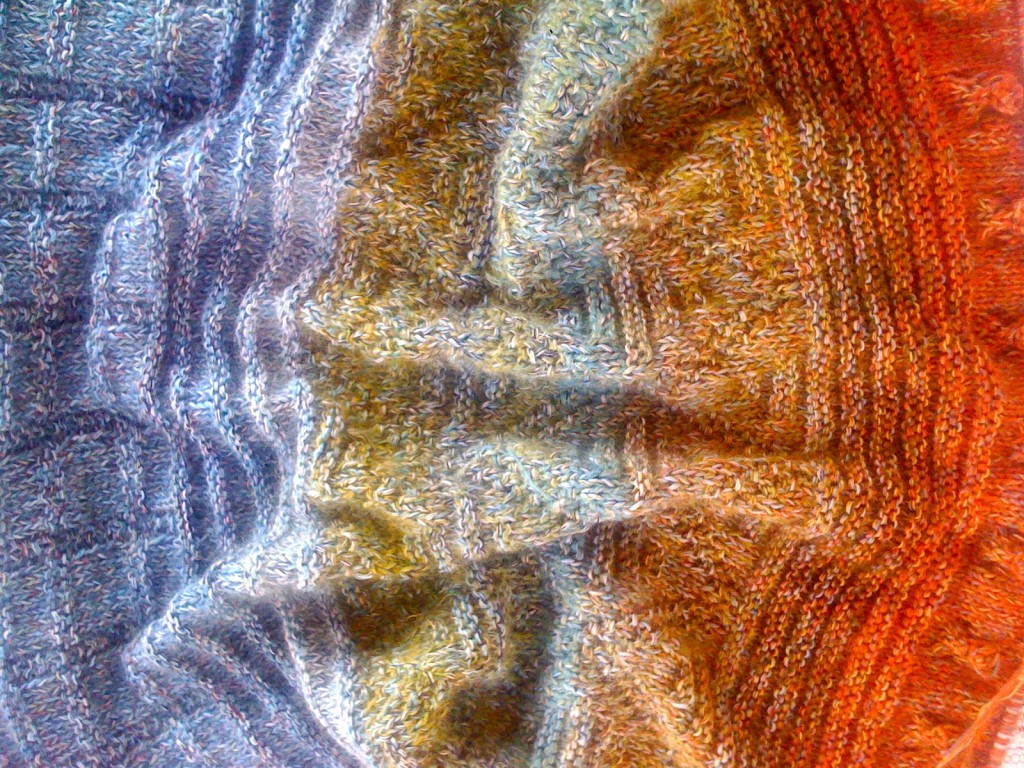

While many knitwear designers might be able to put together similar color palettes, what Inese does with these mohair, cotton, silk and linen yarns makes her absolutely unique. She blends the yarns together as she knits, 6 to maybe 20 at a time, starting in one part of the color spectrum, morphing and shifting the colors as the spirit moves her. While many knitwear designers might be able to put together similar color palettes, what Inese does with these mohair, cotton, silk and linen yarns makes her absolutely unique. She blends the yarns together as she knits, 6 to maybe 20 at a time, starting in one part of the color spectrum, morphing and shifting the colors as the spirit moves her.

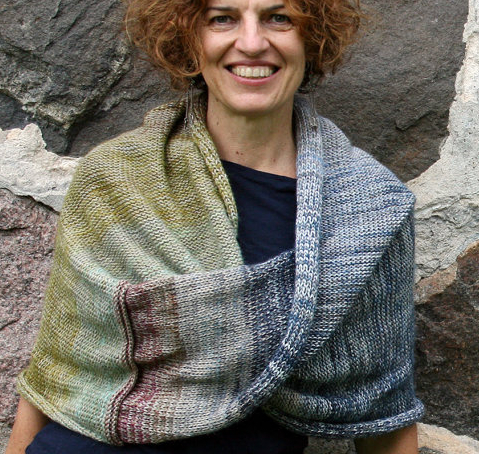

Her passionate play with combinations and moods, usually based on a vision from nature – sunsets, rivers, forests, suggested by her frequent jaunts into the landscapes surrounding Riga – are ‘sketched’ into warm wraps, blankets and sweaters, no two alike. In fact, though she’s tried, even she can’t copy her own work. It’s that one of a kind.

Last month Inese came to visit, bringing me a gift of a large cafe wrap she’s been knitting for a slow food chef in Riga, who wanted to pamper his guests with a wrap of luxurious warmth to ward off the chill in his restaurant’s garden while they enjoyed his meals. At about 500 grams of softness, these are heaven to snuggle into as winter approaches. Last month Inese came to visit, bringing me a gift of a large cafe wrap she’s been knitting for a slow food chef in Riga, who wanted to pamper his guests with a wrap of luxurious warmth to ward off the chill in his restaurant’s garden while they enjoyed his meals. At about 500 grams of softness, these are heaven to snuggle into as winter approaches.

She also brought me two windings, enough to knit another wrap, and asked me to write a pattern for handknitting. As she explains at her Etsy shop: “Everyone who knits declares that they will copy my wraps and knit their own. Then they ask me the instructions and I say, but you can’t copy my yarns or colors. Even I can’t copy my colors, that’s why there are no two wraps exactly alike. Oh – – – true, ummm…”

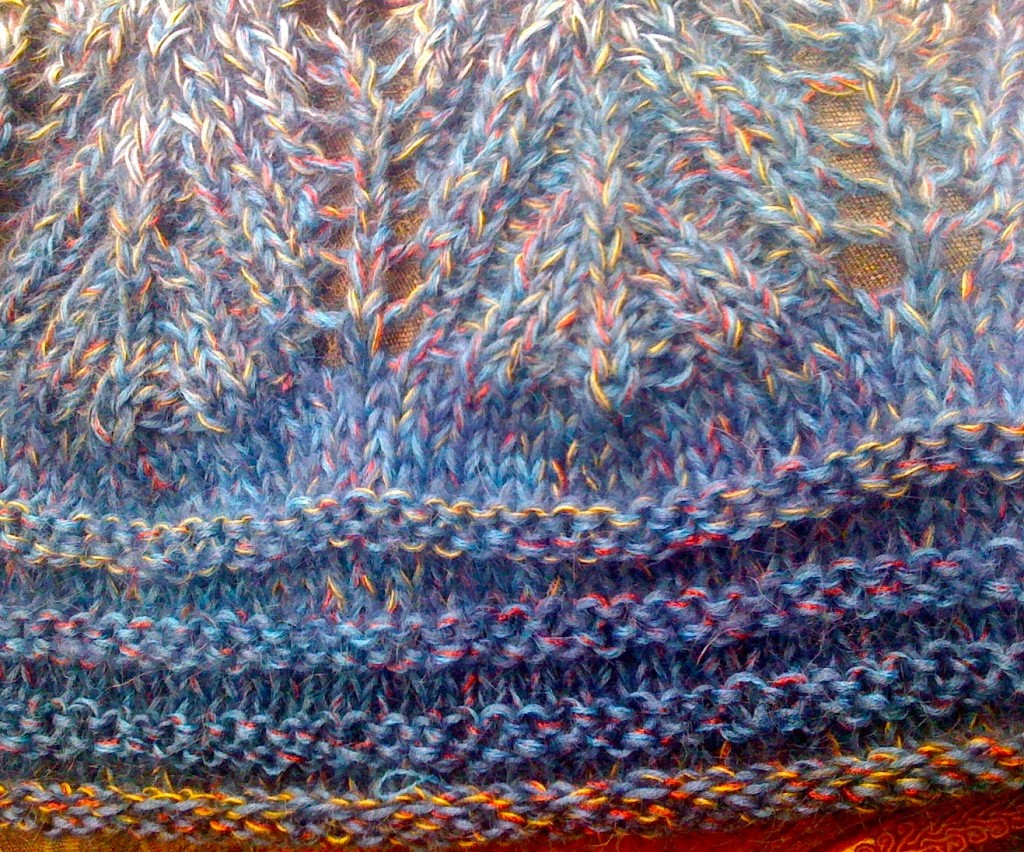

Write the pattern I did, launching a DIY category of knit kits, perfect for gifting knitters who will love the enticing way Inese’s yarns lead from one color to the next, addictive in their meandering flow. Not only did I hate to put my needles down, I wanted to play with texture and pattern. These pictures chronicle my experiments with stitches, as I knit my way along Inese’s rainbow. Write the pattern I did, launching a DIY category of knit kits, perfect for gifting knitters who will love the enticing way Inese’s yarns lead from one color to the next, addictive in their meandering flow. Not only did I hate to put my needles down, I wanted to play with texture and pattern. These pictures chronicle my experiments with stitches, as I knit my way along Inese’s rainbow.

With wonderful materials to work with, there are no ‘wrong’ patterns, though some show color transition better than others. While Inese knits her wraps on a hand loom in stockinette or garter stitches, I added shadows and diamonds, ridges and eyelets to suit my decorative eye. Gilding the lily? Why not! The pic above reminds me of the tiles in the Topkapi Palace. With wonderful materials to work with, there are no ‘wrong’ patterns, though some show color transition better than others. While Inese knits her wraps on a hand loom in stockinette or garter stitches, I added shadows and diamonds, ridges and eyelets to suit my decorative eye. Gilding the lily? Why not! The pic above reminds me of the tiles in the Topkapi Palace.

Visible softness sketched here as colors progress from a sandy beach to lapping waves, a fringe of trees against a cloudless sky at sunset. Visible softness sketched here as colors progress from a sandy beach to lapping waves, a fringe of trees against a cloudless sky at sunset.

Tried and unraveled: my favorite lace pattern of the moment, a chevron rib bordered by a eyelet stripes, morphed from a wide band… Tried and unraveled: my favorite lace pattern of the moment, a chevron rib bordered by a eyelet stripes, morphed from a wide band…

…to a narrow edge finish, with a Gothic arch zigzag and a few more purled ridges stitched in. …to a narrow edge finish, with a Gothic arch zigzag and a few more purled ridges stitched in.

The end result – though this project of embellishing Inese’s imaginative windings has just begun – was a sampler of pattern, from which we’ll create a collection of kits. The end result – though this project of embellishing Inese’s imaginative windings has just begun – was a sampler of pattern, from which we’ll create a collection of kits.

In addition to selling in our Etsy shops, we have exciting news to come about another place we’ll share our collaboration in kits and workshops. More soon! In addition to selling in our Etsy shops, we have exciting news to come about another place we’ll share our collaboration in kits and workshops. More soon!

As the friend who introduced us wrote: “I just have a strong feeling you ladies will hit it off, and as super driven and talented American ex-pats could be a design powerhouse together.”

That power is in full color, the right hues mingling cultures and influences. A universal power to adorn, connect and best of all, play. That power is in full color, the right hues mingling cultures and influences. A universal power to adorn, connect and best of all, play.

Inese photographs and models most of her work, this summer doing a charming photo shoot with a friend, her mother and her daughters. Great design spans generations. All of us need beauty, warmth, comfort and family. Inese photographs and models most of her work, this summer doing a charming photo shoot with a friend, her mother and her daughters. Great design spans generations. All of us need beauty, warmth, comfort and family.

Read the stories she knits up about each piece in her shop… Read the stories she knits up about each piece in her shop…

And if you’re a knitter, join us in playing with color…just click on each pic! And if you’re a knitter, join us in playing with color…just click on each pic!

The old town in Midyat, with church towers dotting the horizon Our next wander on the Tulip Trip was among the stone houses once and maybe still belonging to families of Syriac/Suryani Christians – not to be confused with residents of Syria. Many of those who survived the horrors of World War I moved to Europe as part of the Guestworker era of the 1960’s and ‘70’s. Midyat in Mardin Province traces its roots back to the 9th C BCE, part of at least 12 empires that ruled this region of Tur Abdin.

Large stone houses under restoration Unlike the ‘ghosts’ of Derik, Midyat, like much larger Mardin, boasted an expanding new quarter of town, making the route to the old city almost unrecognizable from a previous visit not so many years ago. But we drove quickly through, wanting to see the changes in the old city.

Some of the old houses seemed abandoned, while others were occupied. Several of the grander homes were being restored into hotels. We trespassed through one unlocked large house that seemed an addition to an adjacent hotel; perhaps it will be a private home instead. Some of the old houses seemed abandoned, while others were occupied. Several of the grander homes were being restored into hotels. We trespassed through one unlocked large house that seemed an addition to an adjacent hotel; perhaps it will be a private home instead.

Signs of former wealth with large rooms, high vaulted ceilings and stone carvings. Modern plumbing was being installed, with walls and floors awaiting restoration. Signs of former wealth with large rooms, high vaulted ceilings and stone carvings. Modern plumbing was being installed, with walls and floors awaiting restoration.

Back outside, a family walking by told Abit they were Syriacs who had been living in Jordan but were thinking about moving to Midyat, where their families had originated. I had to smile at the small worldness of his shirt, with my birthplace of Santa Barbara in far off California printed on the back. Back outside, a family walking by told Abit they were Syriacs who had been living in Jordan but were thinking about moving to Midyat, where their families had originated. I had to smile at the small worldness of his shirt, with my birthplace of Santa Barbara in far off California printed on the back.

More evidence of restoration and enrichment was nearby in one of Tur Abdin’s dozens of ancient monasteries. Mor Abraham and Mor Hobel (Abel), dedicated to two 5th C monks, was now protected by a massive stone wall after vandalism had kept it closed for decades. It was again open to visitors, that day attracting groups of local Suriani youth. More evidence of restoration and enrichment was nearby in one of Tur Abdin’s dozens of ancient monasteries. Mor Abraham and Mor Hobel (Abel), dedicated to two 5th C monks, was now protected by a massive stone wall after vandalism had kept it closed for decades. It was again open to visitors, that day attracting groups of local Suriani youth.

Though I didn’t take a pic, a large refugee camp with hundreds of white tents was under construction behind the church compound. A recent BBC article explained it was not the work of the Turkish government, with Turkish border lands currently inundated with refugees from the Syrian civil war:

“What about that smart refugee camp outside Midyat?” I ask him. “It looked brand-new but half empty.”

“It is for Syriac Christians,” Father Joaqim explains. “The land was donated by a Syriac businessman. Like us, he hopes many Syriac Christians from Syria will come with their families and settle here. Thank God for them.”

Who could have imagined that in a remote corner of eastern Turkey, the war in Syria would be reuniting an ancient community? Only Father Joaqim, perhaps.”

Cross stitch embroidery inside the church Mor Gabriel, a larger monastery just outside Midyat, had been embattled for years in court by government-backed village families claiming the 1700-year-old buildings were “occupying” their land. There are many age-old ethnic and religious struggles still to be resolved in this region. Though as I write this in October 2013, Mor Gabriel has just been returned to the Syriac community as part of “democratization package” currently being unveiled by Turkey’s ruling party, thanks in no small part to a decision by the European Court of Human Rights.

Giving Father Joaqim further reason for optimism, I hope.

Go fly a kite: an assortment of bright paper creatures were flying above the Mardin Museum The Turkish Tulip Trip continues, this time to the city of Mardin

Traveling in Southeastern Turkey may not be easy. Overcoming culture shock, covering long distances, walking in hot weather with little shade on uneven pavements, adjusting to different microbes in the food, just to name a few challenges. Even talking about going to that part of Turkey before our trip brought out all the usual warnings and concerns, about PKK terrorism and the ongoing civil war in Syria, though we were headed well east of the embattled border areas.

Driving east from Ambarli Koyu through flat terrain along the Turkish/Syrian border, it’s a short jaunt north and up 1000 meters to the city of Mardin. Gold limestone buildings on a rocky crag topped by a large NATO-commanded citadel, Mardin, which means “fortresses” in Syriac, looked like a vision out of a child’s book of fables. At first glance, camels laden with opulent goods for the bazaar, or men with long robes and turbans would not seem out of place.

Seeking the Sahmeran: a mythical half woman, half snake, seen in multiple craft incarnations around town. However, we quickly discovered the long main street was lined with Syriac wine shops and chic boutique hotels in those stone buildings, some renovated, others still falling to ruin, but the busy mood foretold that would not be for long. Organizations like the Sabanci Museum are open here, with website translations – to come I suppose, since they don’t yet work – in English, Arabic, French and German. Those surprising wine shops reminded me how the residents of Aegean Sirince helped their village prosper quickly by attracting foreign tourists. Mardin’s current population consists of Kurdish, Turkish, Arabic, Laz and Suriani Christian residents. This upper Mesopotamian city has been settled by numerous civilizations since about 3500 BCE, but Mardin of today seems nearly cosmopolitan, unlike the conservative vibe of Urfa.

More evidence of a returning/growing Suriani community at the newly enlarged and restored Mor Zafaran, a monastery on the eastern outskirts of the city. A modern version of the language of Jesus Christ, Aramean is still spoken in this region of Tur Abdin, which means “servants of God”. I wonder if Abit’s parents named him for it, since relatives call him Abidin.

Hammered nailheads in a door become an abstract work of art

The monastery dates from the 5th century, built on the site of a temple to the sun. Zoroastrians before the Romans perhaps? The fact that the monastery not only has its own website – Turkish only for now – AND a #1 rating on Trip Advisor indicates growing tourism to the area, but the many visitors that day were either Suriani or Turkish.

Returning to our cozy restored Armenian guesthouse, after no Internet access the prior 48 village hours, getting caught up on news from our Istanbul home was a shock. Facebook and Twitter were buzzing with the Gezi Park protests, turned violent enough that friends were admonishing me to stop posting pics from our trip.

Taksim Square has commonly been the site of demonstrations, typically labor union or student gatherings. Something bigger was erupting this time, but it was far too soon – then, and even today – to tell if the outcome will be an ominous regression or a permanent awakening. Wanting to satisfy my political curiosity, I had to postpone learning more until we returned home. But such an odd feeling being in the ‘dangerous’ Southeast, for all appearances peaceful and prospering as of that week in early June 2013, while tear gas and water cannons had taken over Istanbul streets.

Stills from a video, but a colorful night full of dance, music and food Perceptions were further skewed when we were invited to an engagement party in an old carvansaray, now a restaurant managed by one of Abit’s cousins. Hundreds of happy well-dressed people, families and couples, out for a celebration. Hours of dancing, drinking and eating traditional roasted goat, pilaf and cig kofte, food prepared as a festive show of skill by theatrical chefs. Joining us was the Chief of Police, a Euro-styled man in his 30’s, educated in Belgium, fluent in 10 languages and a modern outlook for the future of Mardin. He drove us back to the guesthouse in his late model Mercedes along the quiet after-midnight streets.

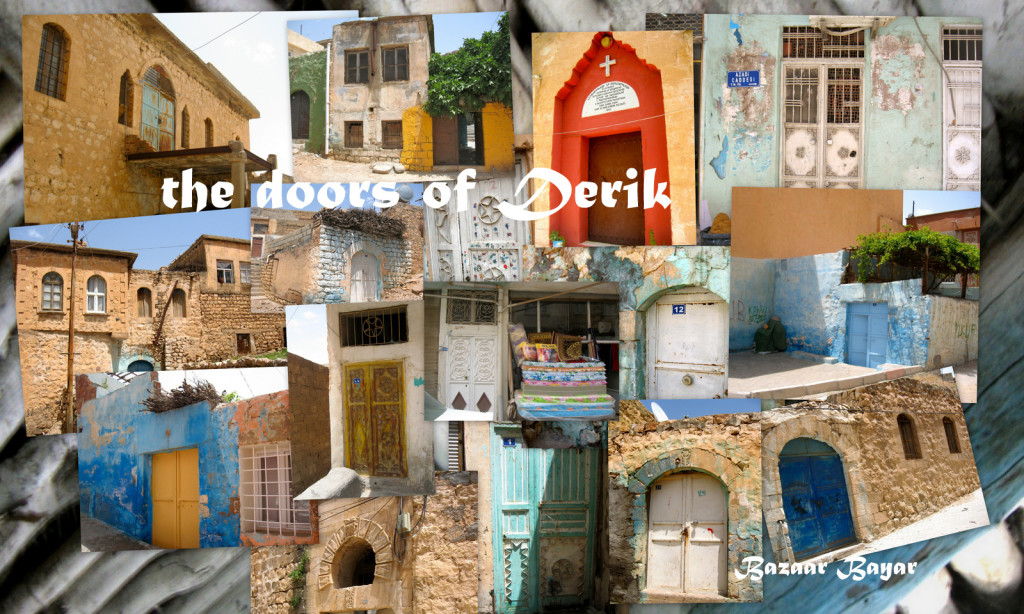

Derik, Mardin Province, Southeastern Turkey After Job and Viransehir, our Turkish Tulip Trip meandered even more decidedly off the beaten path for one more day. We arrived in Derik, a short jaunt north off the international highway leading along the Syrian border from Urfa to Mardin. Derik is the home of Abit’s mother’s side of the family. His father hails from the nearby village of Ambarli; more about it later. A town of about 20,000 surrounded on three sides by stark gold ridges, it’s not exactly ready for tourism. While I can see the economic progress the town has made since my first visit in 1999, this day opened my eyes to the history of the place.

Downtown Derik First stop: our cousins’ butcher shop in the center of town, expanded into the space next door this time, with the usual crew of relatives drinking tea at the back tables. We chatted for some time with one man, a lover of literature, whose English was perfected by years spent in the US and Europe.

For reasons I can’t quite figure, other than pride or politics, Derik seems to be the calendar-producing capitol of eastern Turkey. We were gifted with several different versions, all for this year, depicting local infrastructure improvements and industry, cement factories being most obvious on the printed page as well as along the highway as we came into town. While the butchers prepared a special lunch, we headed up for a stroll in the hilly streets behind.

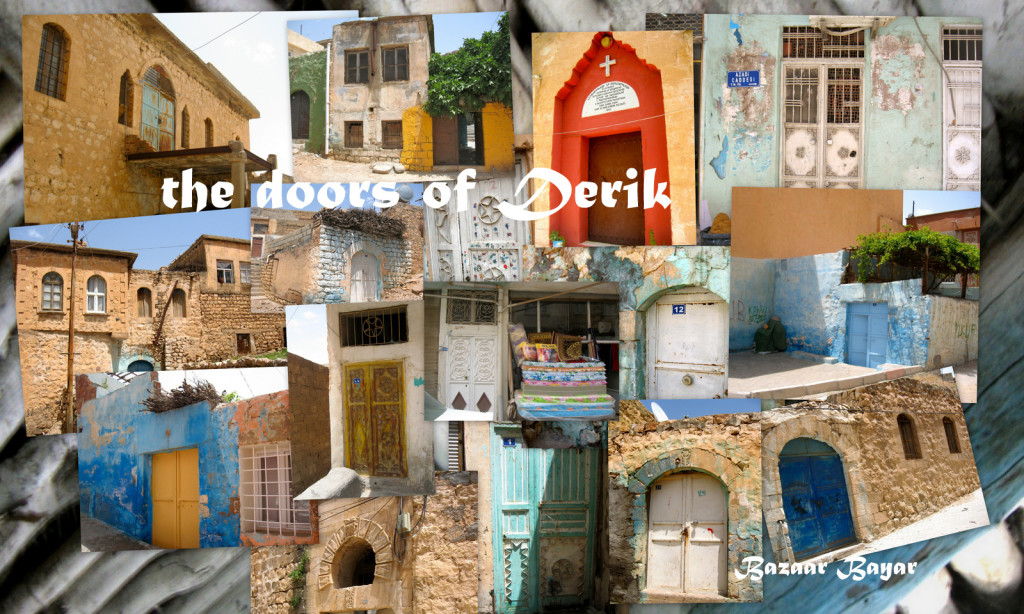

Pigments to paint the doors Half-paved lanes under restoration, half-bright stone houses, old and new, hopeful and sad, more trash than I remembered seeing before. Someone had painted murals of local life on central blank walls, more heartwarming than artistic. The small covered farmer’s market was bustling despite the heat of high noon. Election handbills papered the walls here and there, always with images of the same woman in Kurdish traditional costume or more modern business attire. “Oh, that’s our mayor.” our cousin replied when I asked. “She was elected in 2009 but is in jail, along with 31 other mayors and members of the Kurdish Party, the BDP. The man who spoke English in our shop? That’s her brother.”

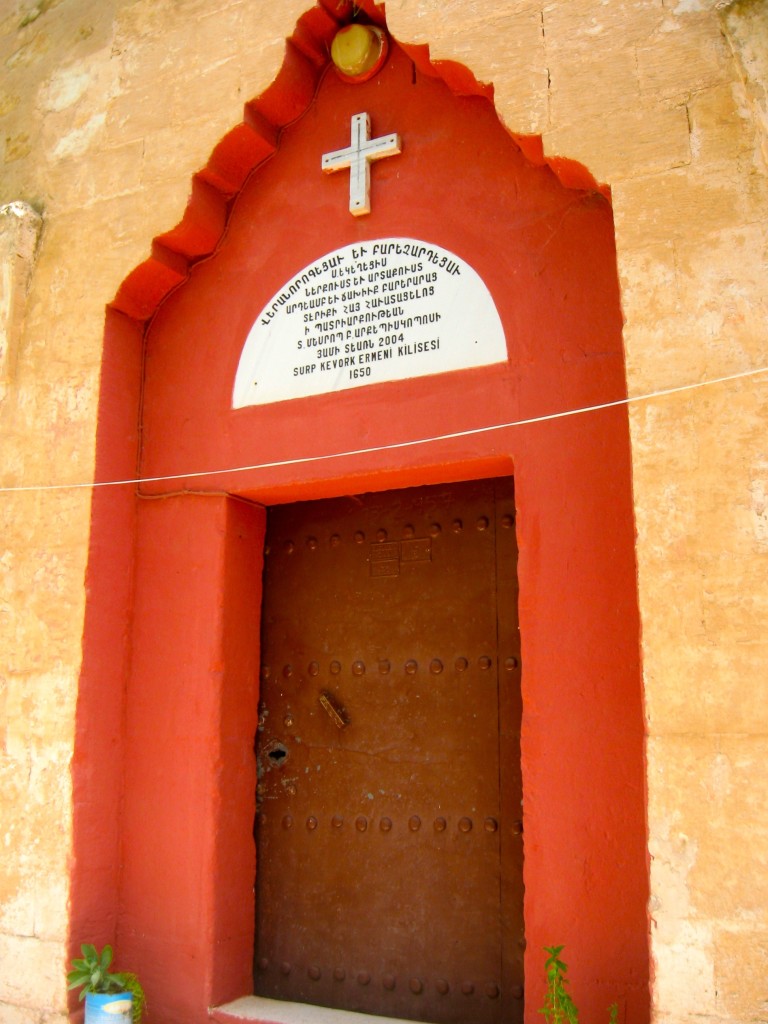

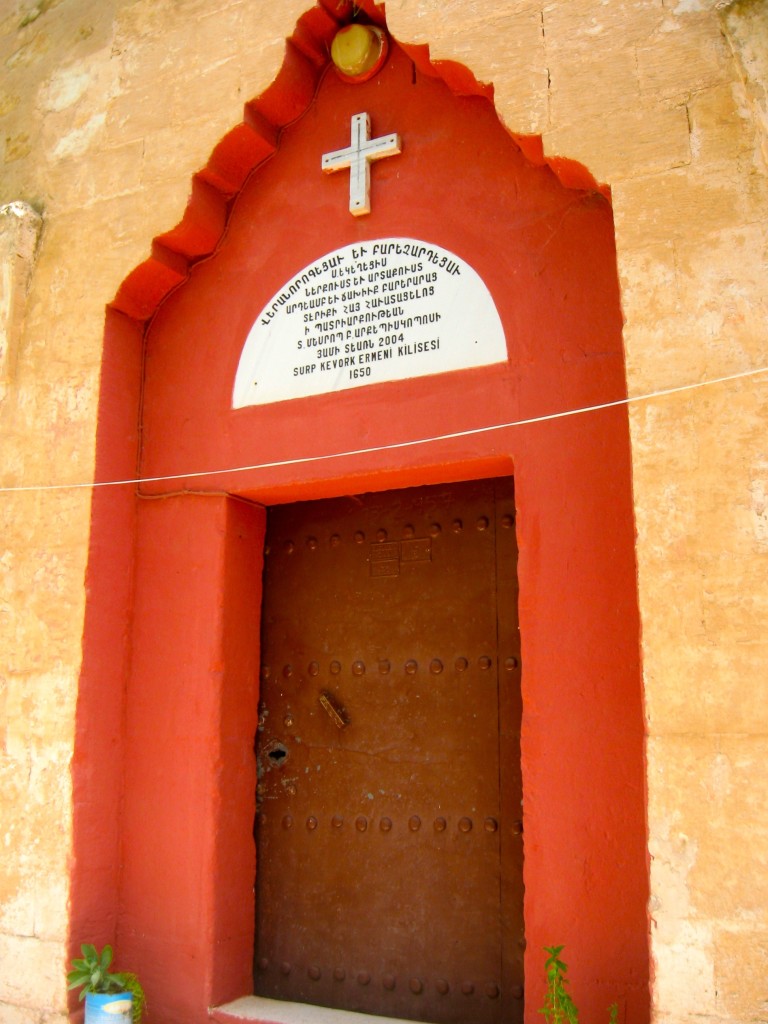

Surp Kevork Ermeni Kilisesi 1650, restored 2004 Into the lane where Abit’s grandfather had his large stone house, though we’d learned that the cousins had just sold it for a more modern place. At least the family that held the keys to the last Armenian Church in Derik was home, a few doors down. Behind the garden gate, a red paint courtyard bloomed with roses and hollyhocks, framing the red door of Surp Kevork (St George) built in 1650.

Under the church The Kurdish Muslim caretaker told us that only one Armenian couple remained in town, then surprised us to say that the church maintenance was paid for by members of the only other Surp Kevork in Turkey, which happens to be a few blocks from our Samatya home in Istanbul; they visit each winter in December. Abit had discovered several relatives from Derik in Samatya when we moved last year, again proving that not just Istanbul but even Turkey itself can feel like the world’s largest village.

Doors of Derik Prior to 1915, Syriac and Armenian Christians inhabited Derik, along with Kurds, Arabs and a few Turks; about the same total number as live in Derik today. A town now almost completely inhabited by former nomads, the Kurds like Abit’s family, though they have no collective memory of ever living anywhere else, other than this town, the surrounding villages, or summers in the surrounding mountains marking the last of the high Turkish plateau north of the vast flat Syrian Plain.

Stone houses As we took pictures in the deserted lanes of Derik, ghosts of residents past lurked in the brightly painted doorways, hiding courtyards to large stone houses, some abandoned, others housing multiple families, all crumbling. Spirits dwell still in those carved stone houses, haunting and magical.

The same feeling I’d had 15 years ago, first seeing the deserted houses near our home in Aegean Selcuk, in the village of Sirince, “abandoned” by the Greeks and repopulated by Balkan Turks during the ‘population exchanges’ of the early 1920’s.

Back in the town center, we ladies needed to freshen up before lunch. Since not many women used the facilities away from their homes, our cousin took us around the corner, to a relative’s house. The sole occupant for the afternoon let us in – a young woman in her 20’s, left to tend house while others in the family were off at work.

Through a ground floor of bare whitewashed arches and rough hewn beamed ceilings, we followed her to the top floor to use the porcelain “a la turka” toilet.

I asked to see the view from the roof. While snapping the town below, I asked how long her family had lived here. “For many years. The house was built by foreigners. But they left.”

“Foreigners? You mean like me, from Europe or America?” I gently teased, though it was no joking matter. “You know, they weren’t foreigners. They were from here too.”

Momentary confusion showed in her eyes. She knew what I meant, though I was a guest who’d just overstepped the bounds of polite hospitality by mentioning something taboo.

“I know,” she admitted. “I’ve heard the stories. It was a long time ago. What can I do about it?”

Perhaps I should not have put her on the spot, but the ghosts were whispering too loudly in my ear.

Escaping the heat and dust of town, Abit and his cousin insisted on eating our simple lunch of grilled lamb, veggies and bread picnic style in the mountains. A struggle to find a four wheel drive up to get us there reminded me that Job’s spirit of patience was something to be cherished here. We made it to the lush setting after ungracefully crossing a small creek running directly from the mountain spring above us. Paradise, yes, but a melancholy one.

One last stop before we continued on to Mardin for the night: Baba’s village. Actually one of three, founded by brothers several generations ago, though this side of the family too says they have ‘always’ lived here.

We followed a few school age girls tending to the cows, herding them out beyond Abit’s father’s wheat fields, ready to be cut. As we drove toward the village, another girl appeared to help us navigate around the newly installed water tower and older pond. No pavement here either, though we later learned the entire village had pooled their resources to install a sewer system to service their a la turka garden toilets. Quick visits to uncles who live in basic village houses, rumored to have more than just new sewer pipes buried in those gardens. But that’s a tale for another time.

I’ve been writing a book about my time in Turkey, my origins and Abit’s, a tale of disparate cultures woven together by shared visions and the love of textiles. Though this was a simple day of visiting family, it revealed threads of understanding I’d not had before. I will be back to listen more to those ghosts. Their tales must be told.

A family visit… More from our spring 2013 Turkish Tulip Trip: Viransehir

Probably the most challenging part of our trip this past spring was not climbing the peak of Nemrut Dagi, or walking around Diyarbakir as a group of very obviously foreign women, or negotiating the often horrendous traffic in Istanbul.

It was spending the night with family. The market town of Viransehir is not exactly a village. The name translates to “ruined city” – it’s been home to and pillaged by numerous civilizations – but it’s certainly village style living in an urbanized setting.

Our plan had been to visit one of Abit’s 6 sisters and her extended family of about 20 people for lunch, but the gods of travel nixed that idea when we got a late start out of Urfa. Our intrepid driver for the day cousin Seyhmus was part of this family and would have been crushed if we’d said no, that we had to push on to Derik that night.

So we arrived late afternoon, to welcoming tea in the family’s current 4 room home on the outskirts of town. Then a tour of the much larger house they were building on the property, which will give the 4 brothers, their father, their wives and children a better environment for living. It was good to see them doing well, though it was obvious they all worked to exhaustion each day, and we were adding to their work. But voicing any objection to spending the night while keeping the peace would have been impossible. Believe me, I’ve tried.

Nieces! This is a country that counts hospitality as a primary function of every citizen. Guests are a gift from God, especially when brought by an eldest brother who is not often in his southeastern home region. The challenge is the not-so-simple matter of culture shock, hot dusty weather, a higher body count per square meter than most visitors are accustomed to, and – not the smallest consideration – a thriving community of mosquitoes, thanks to the surrounding green garden.

Family life like this completely overwhelmed me when I first moved to Turkey. it can still overload my senses now, throwing me back to my early days of acclimation. To be honest, I’ve never truly assimilated. I like my personal space, enjoy being alone, and the family learned it had nothing to do with them. We can laugh about it now.

Breakfast Sitting on the floor, lined with sturdy brightly colored cushions, strewn with rugs and a plastic mat laden with food and tea glasses, or bedding, depending on the time of day. Always people coming in and out, a huge pile of shoes at the front door, a TV on somewhere, a few females chopping veggies and cooking in the kitchen. Conversations involving the entire group, just a few side by side, on a cell phone being passed around – simultaneously. Women knitting, men rolling cigarettes, children being children. The warm loving chaos of our quite typical Kurdish family is a cultural touchstone I like to share with our visitors, but in small doses.

Knitting family style Further to our already disrupted plans was the news that the best knitter in Abit’s father’s village of Ambarli, where we were due the next day, had left for Western Turkey to be with her daughter, expecting the birth of a child any minute. But those gods of travel intervened once more: my favorite knitter and former Selcuk shop inspiration for knitted goods, Azize Hala (which means Auntie on your mother’s side) happened to be visiting Viransehir too.

Instant friends That night, Azize’s slippers became the random mascot of our trip. She is the master among Abit’s mom and her sisters, prolific in the number of styles and patterns she can turn out. She and the other women in our family used to sit with me in our textile shop. More often than not, tourists would walk in to see what we were doing. Our knitting ladies made us the envy of all shops in Selcuk, enticing customers with just-off-the-needle socks instead of repelling them with tired come-on carpet selling lines.

Village slippers Turkish style knitting involves show and tell. No patterns are written, or when they are, assume the knitter will figure most details like sizing out for herself, so are generally rather vague. What most amazes me is the engineering of slippers like these. Done on double pointed needles in whatever quantity best works for each section, they start on top of the foot, shape snuggly around the toes, continue sides and sole at the same time, then neatly fit it all together around the heel and up the back. Seamlessly, few ends to work in. Patterns and color combinations are limited only by yarn supply and imagination.

Azize’s best Our group watched, worked and adapted Azize’s best design, those lovely purple and cream ones, into our own versions as we traveled. I became obsessed with knitting them in every color of Ikonium Studio’s hand spun natural dyed wools. Coming from countries whose knitters expect detailed charts and instructions noting every last stitch, we found learning to think the details through – in those following days when we’d forgotten what Azize had shown us – a good lesson in working solutions out for ourselves.

When I did finally write the western style pattern for Azize Hala’s slippers, it was a 5-page pdf. A pattern engineered over years of many hands perfecting, a slow world method of creating lasting work. Back to the skills that first connected me with the women of my husband’s family. Translating between cultures through stitches and personal expressions of color, with the inevitable tensions here and there, but ultimately universally understood. Everyone wears slippers.

Ikonium Studios wool; my versions with stripes and dots

|

|

Watercolor: Maracuja Project

Watercolor: Maracuja Project